“Man does not live by murder alone. He needs affection, approval, encouragement and, occasionally, a hearty meal.”

“The only way to get rid of my fears is to make films about them.”

“Some films are slices of life, mine are slices of cake.”

“It’s only a movie, and, after all, we’re all grossly overpaid.”

“Ours not to reason why, ours just to scare the hell out of people.”

“Self-plagiarism is style.” — Hitchcock

The Hitchcock Project

Because I need yet another ongoing blog series involving extensive research and movie-watching, I have decided to spend a year examining the films of Alfred Hitchcock. In preparation for this project, I have read several books (including personal biographies, psychological biographies and critical discussions), spent countless hours scouring the internet for further sources, and assembled a collection of 47 of the 51 major Hitchcock films which I hope to discuss during each week of 2008.

While I already know far more than I did before about the man and his work, and I hope by the end to know more still, I remain merely a passionate amateur. I aspire to produce nothing more than a well-researched and informative, but casual and entertaining, series of discussions about these films. I will use whatever reliable supplementary resources are most readily available to me, but I intend to focus most intently on the films themselves (many of which I will be seeing for the first time this year).

I am not terribly interested, as some of Hitchcock’s more sensational biographers have been, in any personal phobias, repressions, fetishes or what have you that could have influenced the great director’s work. My chief interest is in the distinctive skill and artistry which Hitchcock brought to the images which fill the screen during any given moment during his films. I hope that by the end of this project, I and my readers will have a new appreciation for Hitchcock and his films, both greater and lesser.

Early Life & Career

Alfred Joseph Hitchcock was born on August 13, 1899 to William, an Essex greengrocer like his father before him, and his wife Emma Jane. Alfred was the last of three children, three years younger than his sister Ellen Kathleen (“Nellie”) and seven years younger than brother William, Jr. His parents were hard-working and respectable, but they also loved the theater and would often take young Alfred along with them. He was a solitary child, not well-liked by his peers and given to developing his own interests alone. He disliked both of his names, and went by “Hitch” at school. As an adult he would introduce himself cheekily (only to men) with “Call me Hitch, without a cock.”

Throughout his career, Hitchcock often told a story of when he was perhaps six years old. He set out to follow the tram tracks near his house late in the afternoon. Before long, darkness had fallen and he realized he would be late for dinner. Hurrying home, he found his father angrily waiting to begin eating. William gave his son a note to take down to the local constabulary. When he arrived, the desk sergeant read the note and then locked the boy in a cell for 5, perhaps 10, minutes. When he was let out, he was told, “This is what we do to naughty boys.” Although it didn’t occur to him at the time, he eventually realized “perhaps [my father] was angry because he was worried about me.” Hitch went on to joke that he wanted the policeman’s final admonition placed on his tombstone. Nevertheless, the experience strengthened a life-long fear of policemen, and he had a morbid fascination for stories of wrongful accusation and imprisonment.

Hitchcock’s mother was a devout Roman Catholic, and at age 11 he was sent to attend St. Ignatius College, a Jesuit school in London. Hitch credited his religious schooling with investing in him “a consciousness of good and evil,” among other things. Then, shortly after World War I (or, rather, “The Great War”) broke out in 1914, Hitchcock’s father died very suddenly of a heart attack. He was 52 years old. William, Jr. took over the grocery, and Alfred had to give some consideration to what he wanted to do with his life.

His interests led him to a school of navigation and engineering, where he had vague dreams of becoming an aviation navigator. One of his greatest fascinations was with various systems of transportation. He knew the London underground system like the back of his hand at a very early age, and kept well-ordered collections of maps, timetables, schedules and other travel-related paraphernalia. He even memorized the New York subway routes decades before he ever visited the city. Nevertheless, his real talent was for drawing, and he made high marks in his drafting courses. This skill that would later come in handy when he decided to break into the fledgling British movie business. Meanwhile, he also started taking evening courses in art at Goldsmiths College.

Soon, he was hired by W.T. Henley Telegraph and Cable Company thanks to his electrical knowledge and the wartime labor shortage. In 1917, as soon as he had turned 18, Hitchcock presented himself to the army, eager to serve his country. They turned him down. The report noted that he was “overweight, with a glandular condition, and still disturbed by his father’s death.” Hitch was crestfallen. Meanwhile, however, he continued to move up in the telegraph company. Growing tired of the technical side of the business, he joined the sales department, and before long he was drafted into company advertising.

Thanks to his aptitude for drawing, Hitchcock was a perfect fit. A natural storyteller as well as an artist, he also both edited and contributed to the “Henley Telegraph,” his company’s in-house magazine, and produced it so successfully that it was sold outside the business. In the very first issue he published “Gas,” a short story about an Englishwoman visiting Paris who finds herself abducted, robbed and left for dead in the river Seine, only to wake up and find she dreamed the whole experience while anesthetized at the dentist’s office.

Thanks to his aptitude for drawing, Hitchcock was a perfect fit. A natural storyteller as well as an artist, he also both edited and contributed to the “Henley Telegraph,” his company’s in-house magazine, and produced it so successfully that it was sold outside the business. In the very first issue he published “Gas,” a short story about an Englishwoman visiting Paris who finds herself abducted, robbed and left for dead in the river Seine, only to wake up and find she dreamed the whole experience while anesthetized at the dentist’s office.

It’s anyone’s guess where Hitchcock might have ended up by following the track he was on, but in 1919 a new opportunity presented itself. Hitch spotted an ad for a studio called Famous Players-Lasky which was opening a London Branch at Islington. A little insider information revealed what their first film would be, and Hitchcock burned the midnight oil for several nights running preparing an impressive portfolio of title cards for The Sorrows of Satan (based on a novel). Then, he called up the studio and rather brashly offered them his work, completely free of charge. The gambit payed off, and he was hired part-time to design more intertitles for a variety of silent films.

With a boundless enthusiasm for the business, Hitch made his presence felt all over the studio, volunteering for everything and learning all he could. Before long, he was asked to leave his old job with W.T. Henley (which he’d continued to keep) and join Famous Players-Lasky full time. Officially, his job for the next few years (from 1920 to 1922) was to design the intertitles, though in reality he continued to volunteer for all sorts of things, including some assistant directing on the side. In 1922, Hitch got his first directing experience on portions of the films Always Tell Your Wife and Number 13, neither of which was released (much to his eventual relief). During that year, the American studio sold the Islington Studios to Gainsborough Pictures, a new British company started by Michael Balcon.

Balcon, one of the giants of early British cinema, hired Hitchcock as assistant director for Gainsborough’s first film, Woman to Woman. Hitchcock also volunteered to write the script and design the sets, both roles he would go on to fill in many of Gainsborough’s early pictures. With so much on his plate, Hitch was permitted to hire an assistant. To fill the role, he chose a young film editor who had been working at Islington since 1916, but who had been laid off when Gainsborough took over. Her name was Alma Reville. The pair worked together for the next few years, and were finally married late in 1926.

in 1926.

By that time, Hitchcock was directing his own pictures and Alma was his closest collaborator. She was involved in every film he ever directed in a variety of roles, and Hitch consulted her about everything. Accepting an important film award near the end of his life, he said “Among those many people who have contributed to my life, I ask permission to mention by name only four people who have given me the most affection appreciation and encouragement […] The first of the four is a film editor. The second is a scriptwriter. The third is the mother of my daughter, Pat. And the fourth is as fine a cook as ever performed miracles in a domestic kitchen. And their names are Alma Reville. […] I share my award, as I have my life, with her.”

The Hitchcock Touch

At a time when American cinema was sucking the life-blood (in the form of audiences) away from home-grown British films, Hitchcock became the savior of Britain’s movie business. At the time he began his directing career, fewer than 5% of films shown in the United Kingdom were British. In 1927, Parliament passed a law requiring that certain quota of British films be screened every year in an effort to boost the flagging industry. In that same year, Alfred Hitchcock completed his first hit thriller, The Lodger (hailed by contemporary audiences as the greatest British film ever made) and, before he was 30 years old, was soon the most recognizable film director in the country.

His films were so popular that, in 1929, he was given charge of the British “talkie.” Even a cursory study of the history of British film reveals that, during the difficult 1920s, Hitchcock is among the most important players in the industry. His films are virtually the only examples of British cinema during those years which have continued to merit preservation and distribution.

His approach to film-making was simple and methodical, and his technical knowledge of every aspect of his craft was immense. Hitch would exhaustively map out every aspect of a film in advance, maintaining (and sometimes fighting for)

an unusual degree of control over the finished product. Before shooting began, Hitchcock would have every frame and angle of the entire movie thought out and storyboarded. In fact, he was known to remark that he found the actual filming process rather boring, because all of the creative work of making the movie had already been completed before the cameras ever started rolling.

On-set he was notably workmanlike and professional, always showing up for filming in a dark suit and tie whether the camera was rolling on a studio back-lot or in the sweltering heat of the Moroccan sun. His overwhelming interest in the technical side of movie-making gave him a reputation among actors as a challenging director to work for, although many found the experience exhilarating and immensely valuable. Hitchcock gave little or no direction to the performers, demanding only that they stick to the script and stay within the frame of his camera, wherever it might move. If they got it wrong, he would offer suggestions, but more often than not he simply moved on to the next scene, leaving his actors to surmise that his lack of comment meant they had gotten it right.

He hated method actors, expecting the characters to be delivered as they were written and imagined in the script. Ingrid Bergman, who worked with Hitchcock several times throughout the 1940s, once approached him with a difficulty about one of her scenes. “I don’t know if I can give you that emotion,” she told him. “Ingrid,” he replied curtly, “fake it.” He was often quoted as having said that “Actors are cattle,” an accusation many who worked with him had no trouble believing, but Hitchcock himself always denied ever having uttered any such thing. “What I probably said,” he protested, “was that actors should be treated like cattle.”

Cameramen, on the other hand, loved working with Hitchcock because, unlike many other directors, he knew what could and could not be done. He very often presented crews with interesting challenges even as he put his own expertise to work in helping solve them, and the results were innovative and distinctive. Indeed, more than a few of Hitchcock’s films seem to revolve around a series of technical challenges which he has set himself to overcome, and he was never interested in what he called “pictures of people talking.” He also despised an early trend he noted in British cinema of films that looked as though they had been made by merely placing a stationary camera in front of a stage. He had an immediate and intuitive grasp of the possibilities of cinema as an art form all its own, rather than merely as an extension of live theater.

This can be traced, no doubt, to the artistic imagination he developed in his youth. His flair for the visual was further strengthened during the decade he spent working in the silent era, and he never really lost the sense that, in a movie, one should never tell an audience anything when one could show them instead. Fast-forward to almost any of Hitchcock’s best-known scenes and you will immediately notice that, if there is any dialogue, it is purely incidental to the subtext of whatever the camera is watching.

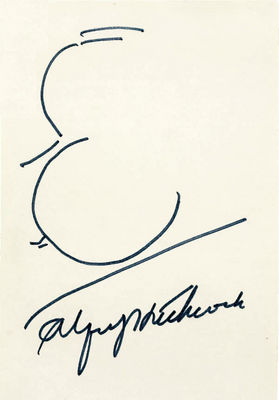

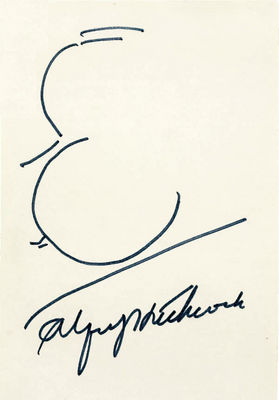

Alfred Hitchcock was one of the first directors recognizable in that role by the general public. At a time when movies were churned out of the major studios primarily as vehicles for big-name stars, it was unique that one went to see “a Hitchcock film” rather than, say, “a Cary Grant movie.” During Hollywood’s “Golden Age,” producers were generally regarded as a film’s primary “creators,” hiring directors to do the grunt work of barking orders on the ground. In this respect, Hitch definitely stood out from the pack. He was widely recognized by sight as well, thanks not only to the famous profile that opened each episode of his television show, but also to his trademark cameos. He appeared briefly in nearly every one of his films, beginning with The Lodger, which he just happened to step in to “simply to fill the screen.” “Later,” he explained, “it became a superstition, and then a gag.”

Alfred Hitchcock was one of the first directors recognizable in that role by the general public. At a time when movies were churned out of the major studios primarily as vehicles for big-name stars, it was unique that one went to see “a Hitchcock film” rather than, say, “a Cary Grant movie.” During Hollywood’s “Golden Age,” producers were generally regarded as a film’s primary “creators,” hiring directors to do the grunt work of barking orders on the ground. In this respect, Hitch definitely stood out from the pack. He was widely recognized by sight as well, thanks not only to the famous profile that opened each episode of his television show, but also to his trademark cameos. He appeared briefly in nearly every one of his films, beginning with The Lodger, which he just happened to step in to “simply to fill the screen.” “Later,” he explained, “it became a superstition, and then a gag.”

When influential French critic François Truffaut and his contemporaries began formulating their revolutionary auteur theory of cinema in the mid-1950s, Hitchcock, along with John Ford, was among their most idolized examples. Essentially, this controversial view of film postulated that the director, more than any other person involved in a movie, was ultimately responsible for the artistry of the best films. Through their personal stylistic flair alone, a good director could elevate even mediocre material into a work of art, infusing it with his or her distinctive touch.

Even today, the most critically-acclaimed films have come to be credited primarily to the skill of the director behind them. However, until the 1970s, with its Coppolas, Scorseses, Spielbergs, and so forth, very few directors achieved the sort of creative control and name recognition that Hitchcock enjoyed for most of his career. Even fewer can lay claim to a body of work as large, cohesive, and perennially-appreciated as Hitchcock’s distinctive films. Critics today still employ his name as an adjective. Those who imitate his style, whether knowingly or not, have their films labeled “Hitchcockian.”

Even today, the most critically-acclaimed films have come to be credited primarily to the skill of the director behind them. However, until the 1970s, with its Coppolas, Scorseses, Spielbergs, and so forth, very few directors achieved the sort of creative control and name recognition that Hitchcock enjoyed for most of his career. Even fewer can lay claim to a body of work as large, cohesive, and perennially-appreciated as Hitchcock’s distinctive films. Critics today still employ his name as an adjective. Those who imitate his style, whether knowingly or not, have their films labeled “Hitchcockian.”

Hitchcock’s work in the movies spanned five decades, from the silents in the 1920s, through early talkies in the 1930s and into the dream factory of the studio system in the 1940s. He transitioned his talent successfully to the demands of television in the 1950s, and flirted heavily with the edge of acceptability before the fall of the production code in the 1960s, finally churning out his final films as younger men ushered the cinema into the modern era in the 1970s. But he left behind him an indelible mark on the genre of which he was and is the uncontested master: the suspense thriller.

Next Week: Hitchcock directs his first film

Posted in Hitchcock, Scholarship

starring Ellen Page, Michael Cera, Jennifer Garner and Jason Bateman

starring Ellen Page, Michael Cera, Jennifer Garner and Jason Bateman

“Tall he was – and his face all wrapped up.”

“Tall he was – and his face all wrapped up.”

“The highly popular reviews at the Pleasure Garden Theater are staged by Mr. Hamilton.”

“The highly popular reviews at the Pleasure Garden Theater are staged by Mr. Hamilton.”