Film History Essentials: The Landing of Savage South Africa at Southampton (1899)

The ship-board contingent was organized and led by Frank Fillis (see right), a London-born showman and entrepreneur who operated a successful South African circus. With him were lions, tigers, elephants, a group of Boer families (Dutch-descended South African settlers), and nearly 200 men (along with a few women and children) from various Bantu tribes, including: Zulu, Swazi, Matabele (Northern Ndebele), and Basuto (Sotho). A number of these tribesmen had reportedly been told that they had been given jobs at the Kimberley diamond mine. Instead, they found themselves transported to London to spend the next several months on display as part of an exhibit titled “Savage South Africa.”

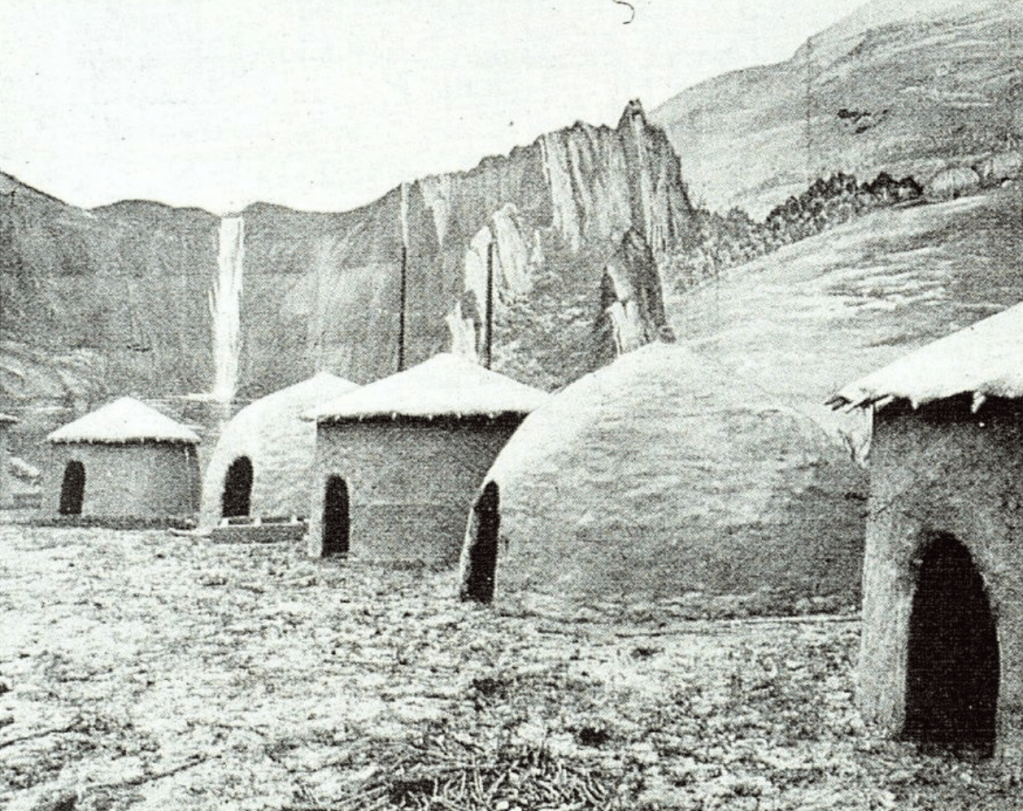

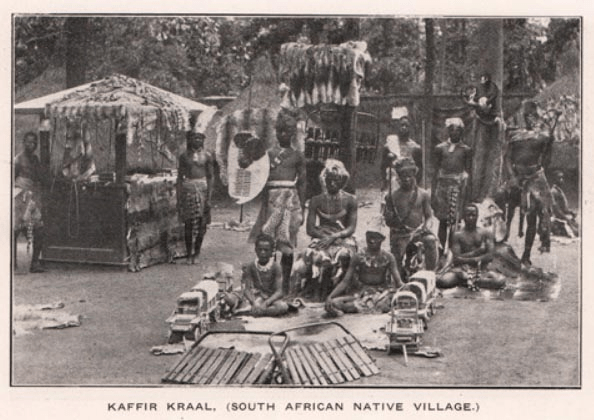

The advertised goal of the exhibit was to give Londoners an “authentic” look at African life. The Africans were housed in a specially-constructed “kraal” or village, consisting of mud huts in front of a painted backdrop of a South African landscape. According to the exhibition guide, the inhabitants were to “live and occupy themselves just as they do in the Bush, or on the veldt of their own native wilds.” The reality, of course, was that the entire display was carefully managed and staged to conform to the expectations of paying attendees.

For centuries, European interest in the African continent was confined to its coast, where passing ships could put in for resupply, or connect with profitable sources of trade in gold, ivory, and slaves. With the dawn of industrialization, and development of treatments for the deadliest tropical diseases, European encroachment into Africa exploded in the last quarter of the 19th century. In what became known as the “Scramble for Africa,” European powers carved up the land between them, taking control of nearly 90% of the continent within a roughly 40-year period.

The process was far from peaceful. The British Army engaged in several conflicts with African tribes, including most of those represented in the “Savage South Africa” exhibition. The British annexed Zululand after the Anglo-Zulu War in 1879. They fought the Ndebele in the First and Second Matabele Wars (in 1893-94 and 1896-97, respectively). The latter conflict ended with Matabeleland being folded into the new colony of Rhodesia in 1898 (now Zambia and Zimbabwe).

The Sotho, too, fought the British occasionally (and were successful more than once). However, after a series of wars with the Boers in the 1860s, the Sotho were forced to ask for British assistance or be overrun, and Basutoland became a British protectorate. The Swazi tried a different tack, aiding the British in various conflicts against other tribes, and granting them numerous concessions of land and mining rights throughout the 1870s and 1880s. The end result was that Swaziland still ended up as a British protectorate in 1894, without the Swazi being consulted about it.

Cultural depictions of these conflicts throughout the period emphasized the individual heroism and sacrifice of often-outnumbered British troops against a “savage” horde of anonymous natives. “Savage South Africa” brought together defeated enemies and subordinated allies to give ordinary British citizens a taste of the glory and adventure of the military expeditions in Africa. In fact, lest anyone be confused about this purpose, performative defeat was also part of the program.

In shows twice a day, at 3:30 and 8pm, after a horseback riding act, the nearly-200 Africans would re-enact events from the Matabele Wars, staging battles with around 20 “British” soldiers (played by the Boers in the troupe who, ironically, would soon be at war with England themselves). These performances are reminiscent of similar staged reenactments between Native Americans and US Cavalry that were part of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West. As with Buffalo Bill’s show, a few of Fillis’s fake battles were also captured on film: Savage South Africa – Savage Attack and Repulse and Major Wilson’s Last Stand (both 1899).

The latter film focused on a famous and celebrated episode (see above) from the First Matabele War. At the end of 1893, the Shangani Patrol, a group of 36 soldiers led by Major Allan Wilson in pursuit of King Lobengula, were ambushed by a force of about 3,000 warriors. Three of the patrol were able to escape and ride for reinforcements, but were unable to return in time. The remaining members of the patrol fought until they ran out of ammunition, reportedly killing several hundred of the enemy, but were then overwhelmed and killed. Lobengula died of smallpox the following month, and the Matabele surrendered soon after.

Here, again, the battle and the propaganda surrounding it calls to mind conflicts between the United States and Native American tribes, notably “Custer’s Last Stand” at the Battle of the Little Bighorn in 1876. Much as Chief Sitting Bull, a participant in that battle, later joined Buffalo Bill’s show, “Savage South Africa” claimed a similar connection. While Frank Fillis himself played Major Wilson, the role of King Lobengula was played by one Peter Kushana Loben, who claimed to be Prince Lobengula, the king’s son (see left). It isn’t clear whether this claim was true or not, but it was accepted during his lifetime.

Although a hit with audiences, “Savage South Africa” was immediately a source of controversy in both the British and colonial governments. Officials expressed concerns about the treatment of the African members of the troupe, and raised questions about whether they had been lured to London under false pretenses, about the supposed educational value of the exhibition, and about the risks posed by having a large number of African tribesmen housed in the middle of London. This last issue led to the largest controversy of all, when Prince Lobengula was involved in a massive scandal a few months after the show opened.

In August, reports emerged that Prince Lobengula was engaged to an Englishwoman, Florence Kate “Kitty” Jewell. The real story of how their relationship started and developed is difficult to extract from the sensationalized accounts that proliferated in the press. It caused such a stir that the minister who had agreed to marry them backed out at the last moment, and their marriage license was revoked.

The couple was able to quietly marry the following year, but the union was apparently a tumultuous one. They divorced early in 1902, with Kitty alleging adultery and physical abuse. Not long after, Peter married Lily Magowan, an Irishwoman, and they settled in Salford, near Manchester. Peter worked a series of jobs and eventually became a coal miner. The couple had five children.

In 1913, Peter was in the news again when he appeared in court, claiming that he was entitled to vote in local elections. The court ruled in his favor, but he was by then suffering from tuberculosis and he died soon after. Within just a few years, Lily and four of his children were dead, as well, though one of the family lived on until 1977.

In the meantime, the interracial relationship was an international story when it broke in 1899, and the entire affair was soon distorted by journalists with a racial axe to grind. A newspaper in Galveston, Texas, reported that “fashionable women” who attended were engaging in “the vilest orgies” in the huts at the exhibit. In response to the controversy, the company in charge of the exhibition ordered that women no longer be admitted to the kraal.

The entire business (including, eventually, the end of Peter and Kitty’s marriage a few years later) was seen as a confirmation of white fear about the the safety and virtue of European women spending time around African men. There are some claims that the scandal ultimately brought an end to the show’s run entirely. However, it isn’t clear whether “Savage South Africa” actually concluded before the rest of the Greater Britain Exhibition.

In any case, the damage must not have been permanent, as the show went on tour around the country the following year. “Savage South Africa” was able to capitalize on increased national interest in the region created by the beginning of the Second Boer War in October 1899. A glowing review from its opening in Sheffield in April 1900 reveals that Peter was still a part of the show over a month after successfully marrying Kitty, and continued to be popular with audiences.

It isn’t clear what became of all the African members of “Savage South Africa” after the conclusion of the tour. At least one, a 19-year old Basuto man named Pasha Liffey, stayed behind and settled in Scotland, where he made a living as a boxer and circus performer. In 1905, he was hanged for the rape and murder of 63-year old Mary Jane Welsh.

As for the rest, if any settled in the United Kingdom they must have lived quieter lives. Some probably returned home, but some certainly must have stayed on with Frank Fillis. He went on to operate a Boer War Exhibit at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair which also included battle re-enactments and tribal villages populated by African people for visitors to gawk at.

Screening:

The Landing of Savage South Africa at Southampton, like the exhibition itself, is almost as significant for what it doesn’t show as for what it does. There’s no indication here that the men on the screen spoke several languages, both European and African. The film shows them in their exhibition costumes, but not what they wore when they weren’t performing for a crowd. It doesn’t show what’s happening off-screen, where several of the men keep glancing hesitantly as they stamp and chant.

Of course, once the white man in the top hat strides into view, it’s possible to guess where the men had been looking. This figure is, of course, Frank Fillis, and in just five seconds he gives a very firm impression of what it must have been like to work for him (at least for these men). He appears impatient, terse, and dismissive here. Above all, it’s clear he is a man with a very particular vision of how this display should look, and he demands that it look exactly that way.

His intrusion into the scene reveals the artifice of the entire enterprise. Ultimately this is a vision of blackness and Africanness that is designed by a white man for consumption by other white men. Both here and in his later show in the United States, Fillis was responsible for shaping thousands of peoples’ impressions of Africa and Africans through their first (and perhaps only) direct interaction with its people. And that impression was not arrived at by accident.

Slightly better copy here http://www.colonialfilm.org.uk/node/1186

LikeLike