Summary:

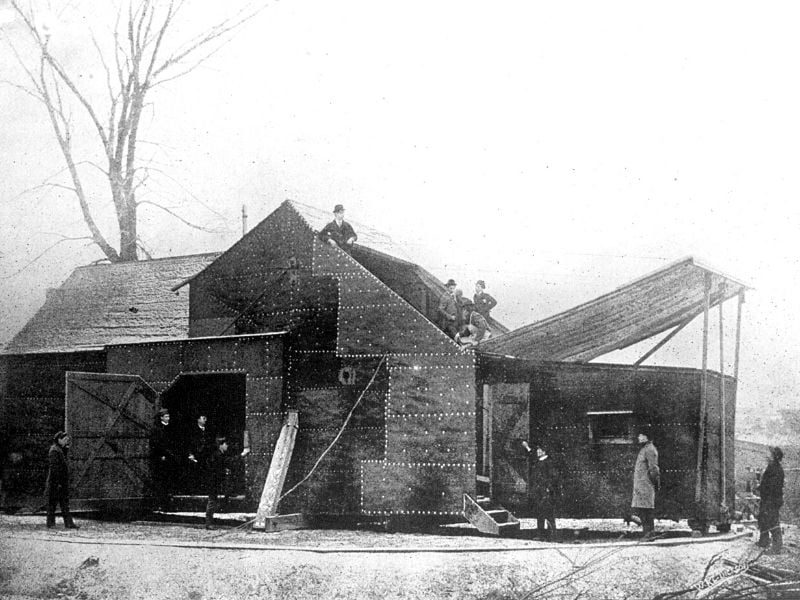

During the winter months of 1892-93, Thomas Edison had a new building constructed in his lab complex at West Orange, NJ. It must have stood out, even before it was completed. The whole structure was covered in black tar paper and had a roof that could swing back to let in the light. Most unusual of all, the building was mounted on a circular rail so that the whole thing could be rotated to follow the sun no matter where it was in the sky. William Dickson and the others who worked in it nicknamed it the “Black Maria,” a slang term for police vans, due to the dark exterior they had in common, and because (they claimed) they were equally uncomfortable to occupy.

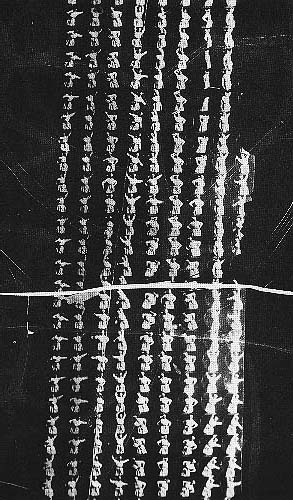

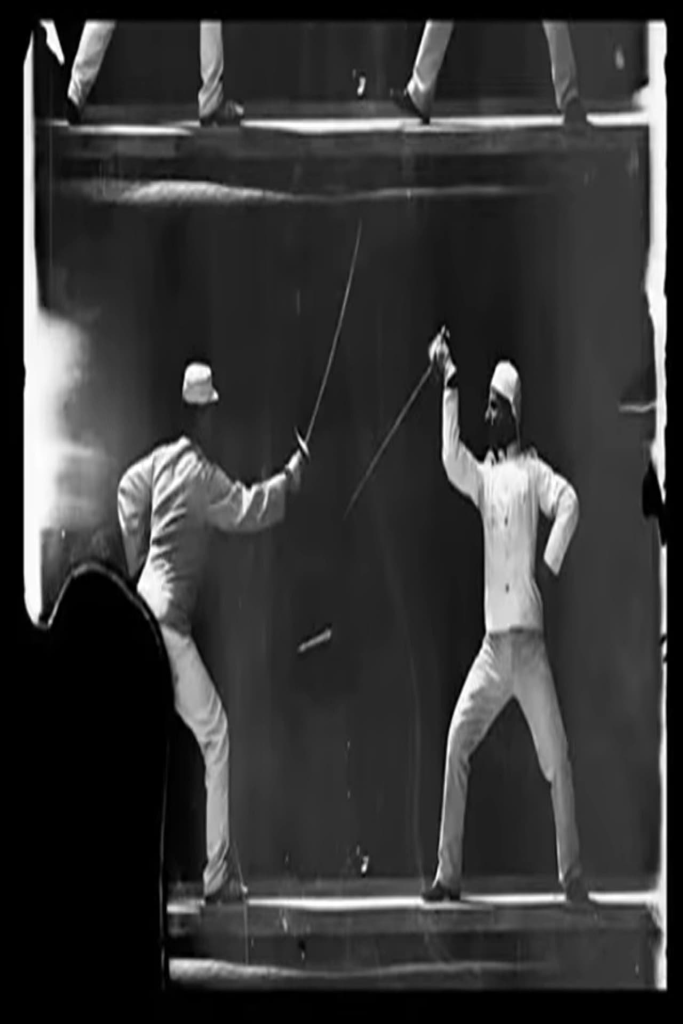

This was the world’s first film production studio, and Dickson and his team got straight to work producing material in preparation for the launch of the kinetoscope. They shot hundreds of films there over the next several years, and all of them have a distinct look. The subjects are usually filmed in a wide shot that frames them head to toe. The deep black background reveals no visible details behind action, absorbing the light and providing a high contrast for any performers in front of it, who are themselves brightly lit by the sunlight coming in from overhead. Viewed through the kinetoscope’s peephole, surrounded by featureless darkness on all sides, I imagine it almost seemed to the viewer as though they were miniature people, inhabiting the box and performing for nickels.

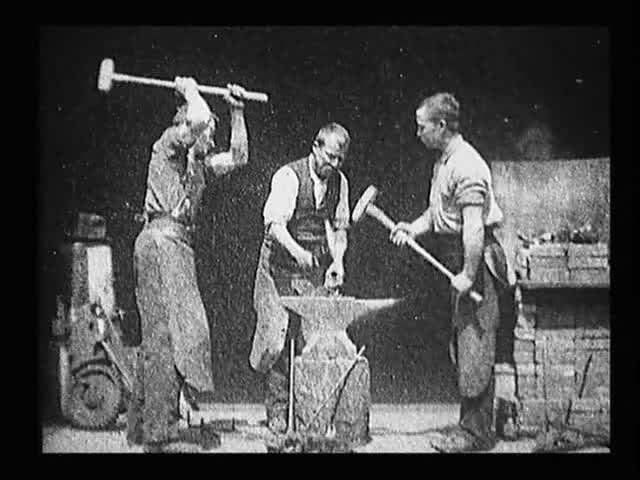

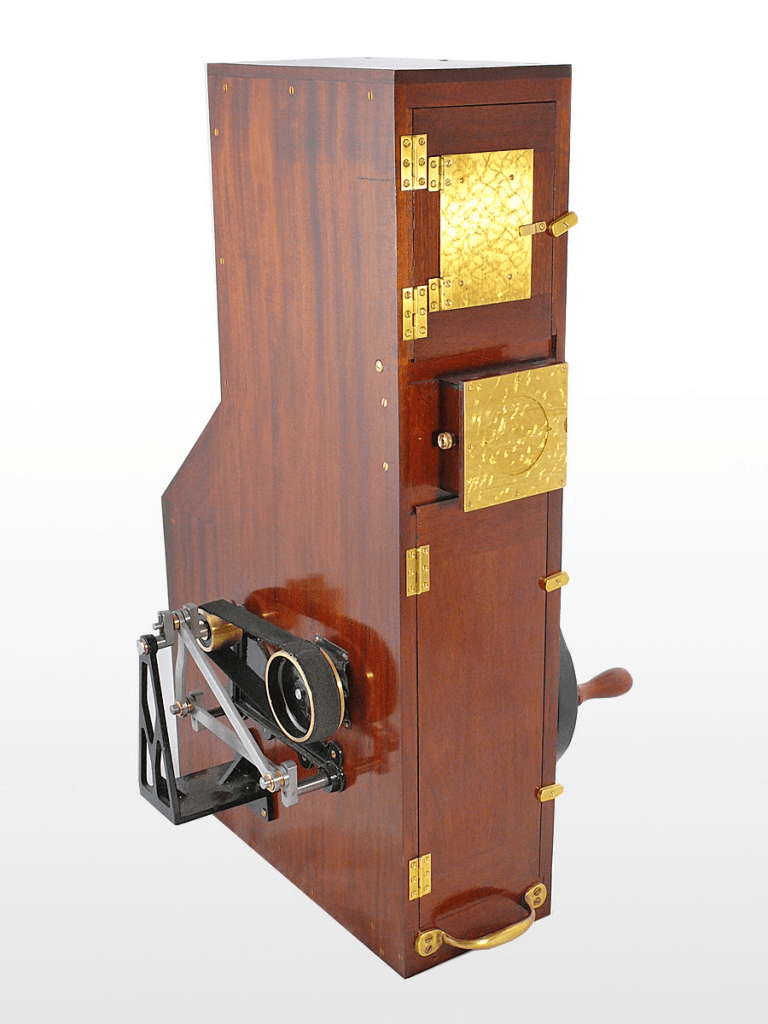

On May 9, 1893, Edison traveled to the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences for the first public exhibition of the kinetoscope. Blacksmith Scene was the very first film to be publicly shown. This is yet another sort-of-but-not-quite arrival of cinema as we know it: The show was an actual live-action film this time, but it wasn’t projected for an audience because the kinetoscope was designed for a single viewer. America’s first movie audience lined up to watch it, one at a time. Before Newark Athlete made the list in 2010, Blacksmith Scene (added in 1995) was the oldest film on the National Film Registry. It’s still the oldest surviving complete film, both on the list and in existence that we know of.

Screening:

I don’t know a thing about blacksmithing, but this certainly looks like the real deal. The outfits and equipment are clearly authentic, and the three men swing their hammers quite convincingly. The way they work as a team stands out particularly. With very little communication between them, they all seem to work in tandem, and not a motion is wasted. It’s almost like choreography. This, it turns out, is a result of planning (and perhaps rehearsal) rather than on-the-job experience. No one in this scene is actually a blacksmith. They’re all employees of Edison’s lab, drafted to be early movie stars. Among its other list of firsts, that also makes this the first filmed performance by actors playing a role (again, that we know of).

You may miss it if you aren’t looking for it, but there’s a 4th person in the scene, as well. I didn’t notice it at first because I’m so used to film deterioration and damage obscuring a part of the image, but the dark area on the left side, partially covering one of the assistants, isn’t that at all: It’s perhaps the first movie blooper. For several seconds at the beginning, someone is standing in front of the camera with their back to it before suddenly stepping out of frame. Whenever I see something like that happen in a very early film, I wonder if it wasn’t reshot because they didn’t think it mattered or that audiences would care, or if the process was too painstaking and expensive to repeat for any but the most disruptive issues. In this case, it may have been both.