William Dickson had begun secretly advising the Lathams in the development of their camera and projector at the beginning of 1895, while still working for Edison. However, he already had a long-standing relationship with another group of men in much the same role. In 1893, Dickson worked with two other men to invent a pocket-watch-sized camera called the Photoret (see right).

One of those two men was Henry Marvin, a college teacher and engineer Dickson had known since the 1880s. The second was Herman Casler, a talented mechanical engineer Dickson had met a few years earlier while he was working on one of Edison’s mining-related projects. (In fact, this project had actually interrupted Dickson’s early work on the kinetoscope for several months.) The Photoret was manufactured, marketed, and sold by Elias Koopman’s Magic Introduction Company, and the result was apparently profitable enough that the partnership continued.

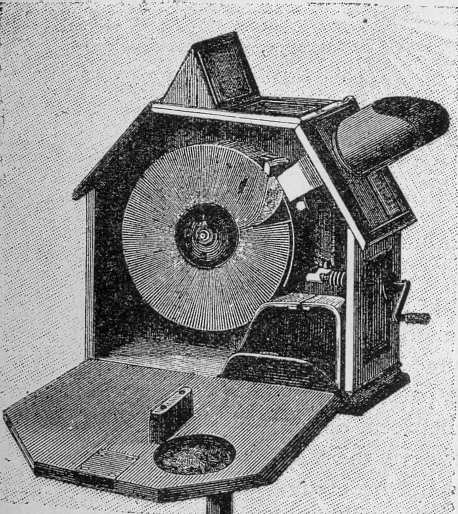

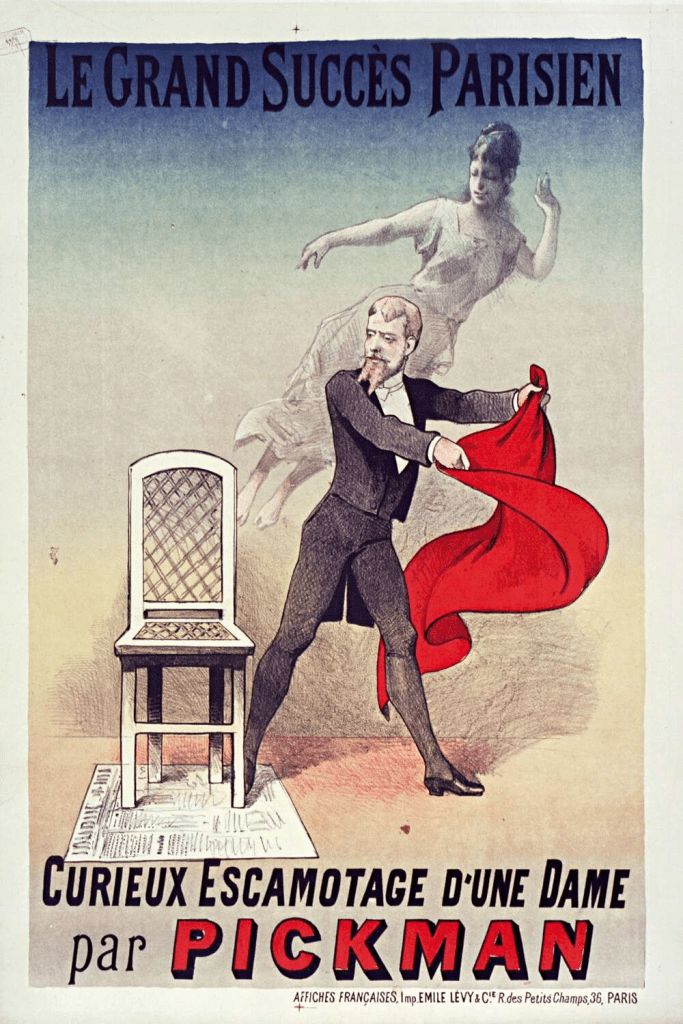

The group’s next project was an idea Edison had rejected for the kinetoscope. Dickson proposed a circular deck of images that would operate much like a large flipbook, with the viewer operating a crank to power the motion of the reel while watching through a peephole. The other men liked the idea, and together they formed the KMCD Syndicate (for Koopman, Marvin, Casler, and Dickson), and Casler went to work developing Dickson’s idea. Casler patented it as the “Mutoscope” in November of 1894, and then spent several months developing a camera that could produce material for it. The Mutoscope was a simpler and cheaper design than the kinetoscope, and it was quite successful, immediately becoming a source of serious competition for Edison’s kinetoscopes.

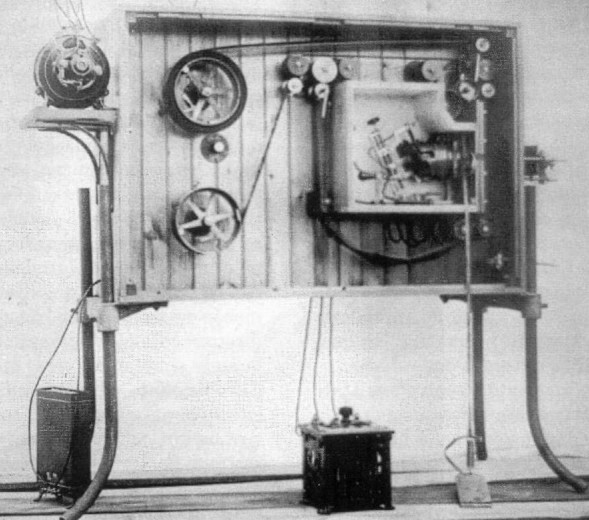

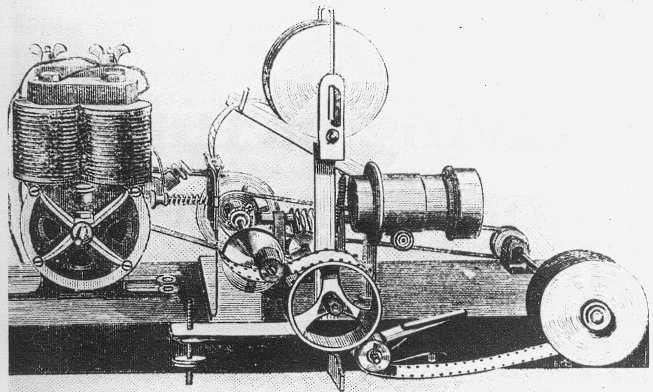

By this time, Dickson had left Edison’s employment, officially joined the Lathams’ Lambda Company for the debut of the Eidoloscope, and then left them as well. He finally joined the other members of the syndicate for their first official meeting as a group in September 1895, and they decided to develop a system for projecting motion pictures. On December 30, 1895, they formed the American Mutoscope Company. Edison had debuted the Vitascope before they were ready to introduce their projector, but by the summer of 1896, the “Biograph” was ready to go. Edison had gotten there first, but the Biograph was noticeably superior in several ways, using the same, wider filmstock as Georges Demenÿ, which produced a much larger image (although its chief benefit was that its use didn’t violate any of Edison’s many patents).

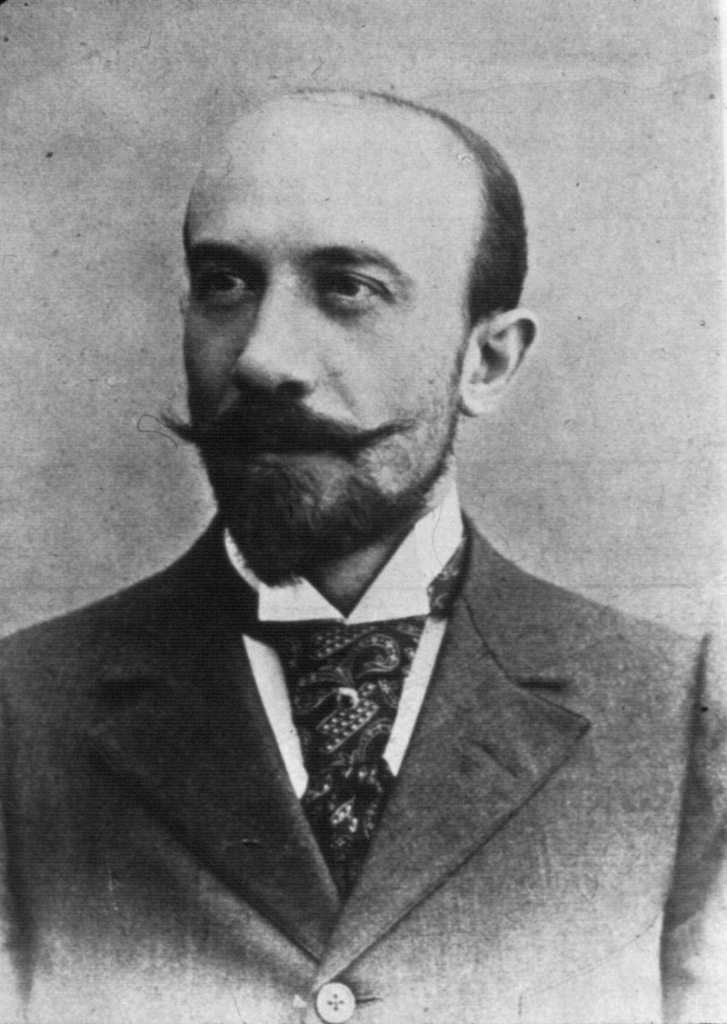

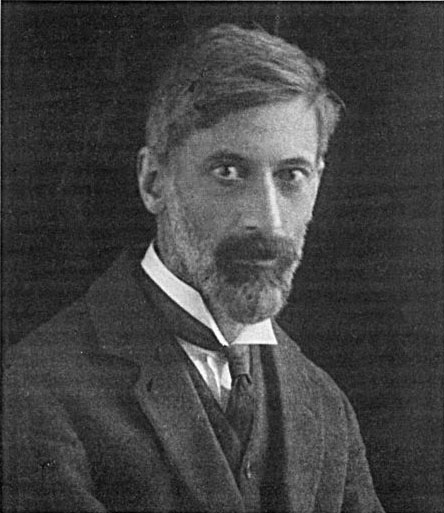

One of the men who invested in this new motion picture enterprise was Joseph Jefferson (see right), one of the most famous actors of the American stage. Jefferson, by then in his mid-60s, was known throughout the country, as well as in Australia and England, for the role of Rip Van Winkle that he had been playing since 1859, and had played virtually exclusively since the mid-1860s. The possibility of leveraging his fame to boost the American Mutoscope Company must have seemed like too good of an opportunity to pass up.

Sometime between the winter of 1895 and the summer of 1896, Dickson collaborated with Jefferson on an adaptation of his stage performance, filmed in eight separately-titled scenes. Played in sequence, they were:

- Rip’s Toast

- Rip Meeting the Dwarf

- Rip and the Dwarf

- Rip Leaving Sleepy Hollow

- Rip’s Toast to Hudson and Crew

- Rip’s Twenty Years’ Sleep

- Awakening of Rip

- Rip Passing Over the Mountain

The company had built a new studio in much the same style as the Black Maria (but located atop a building in Manhattan), but these films were shot “on location” at Jefferson’s home in Buzzards Bay, Massachusetts. Scenes 2 & 3, 5 & 6, and 7 & 8 are all actually single scenes divided into two halves, due to the limitations on how much film the camera could hold. Each of these scenes cuts abruptly at the end of the first half, and then picks up in the same camera position almost exactly where the previous one left off. For instance, scene 5 ends just as Rip throws up his hands and starts to lean backwards, and then scene 6 begins with him continuing to fall completely prone.

The films were released for the Mutoscope, but they were also among the first films offered for projection. They were not sold as a complete package. Exhibitors could pick and choose whichever of the eight scenes they wanted, and then show those scenes in any order they chose. At least some of the eight were also featured in the official debut of the Biograph in the fall of 1896. The series proved quite popular; so much so that, in 1903, the company (by then known as the American Mutoscope and Biograph Company) finally edited them all together and re-released them as a single film. The whole series was added to the National Film Registry in 1995.

Screening:

The Biograph was noted for its superior picture, but sadly, all that survives of this film are the paper prints registered for copyright purposes, which were duplicated at a much lower quality. Further, there is much that was presumably of interest to a turn-of-the-century audience that doesn’t really translate to us. There’s the novelty of simply seeing a projected motion picture, obviously, but also presumably of seeing a famous actor of the day delivering an excerpt of his most famous performance. Certainly the film assumes a prior familiarity with the story of “Rip Van Winkle,” and it doesn’t actually show us the end of the story.

Although it is an incomplete retelling, it is the oldest surviving literary adaptation to film (by way of a stage adaptation). Born in 1829, Jefferson is also likely the film star with the earliest birth year. More notable, though, is that it represents a significant step forward in the length and sophistication of cinematic storytelling. Despite being cobbled together in pieces because of the technical limitations, this is still a multi-scene, multi-minute film narrative, while also being one of the earliest American films to tackle fiction.

I’ve compiled a playlist of all eight short films, in order, that you can watch and navigate through below: