It’s difficult to say just why Escape from the Planet of the Apes, rushed out a mere year after the previous installment, works so well. Maybe it seems better mainly by comparison with Beneath the Planet of the Apes. Maybe it’s the novelty of complete departure from the previously established formula. Because Escape doesn’t just avoid retreading the plots of the previous two movies, it escapes into an entirely different genre.

It’s difficult to say just why Escape from the Planet of the Apes, rushed out a mere year after the previous installment, works so well. Maybe it seems better mainly by comparison with Beneath the Planet of the Apes. Maybe it’s the novelty of complete departure from the previously established formula. Because Escape doesn’t just avoid retreading the plots of the previous two movies, it escapes into an entirely different genre.

If there is an example of a franchise continuing from a deader dead-end than Planet of the Apes did between its second and third movies, I am not aware of it. Beneath ended with the complete and total destruction of earth, and the words, “In one of the countless billions of galaxies in the universe, lies a medium-sized star, and one of its satellites, a green and insignificant planet, is now dead.” How do you make a movie about the Planet of the Apes after the Planet of the Apes blows up?

The solution is so elegant that it seems obvious once you’ve heard it, and it manages to shift the focus of the rest of the franchise onto the titular apes rather than the human protagonists of the previous films. And not just any apes, but (in this case) Cornelius (Roddy McDowall) and Zira (Kim Hunter), the heart and soul of the first film. The result is a perfect mirror image of the original (that’s the formula part I alluded to earlier).

Escape begins with my favorite scene in any of the original Apes movies, and it works flawlessly the way I first saw it. I began it completely cold, after watching the first two films, with no prior knowledge of what the movie would, or even could, be about. The opening shot is of open ocean beyond the coastline, which looks like where the first movie ended and the second began. Then, a helicopter flies into view, which is immediately different. Where is this? When is this? The chopper pilot spots something in the water, and radios back to base, mobilizing an army unit to recover the object. It is a spaceship, very like the craft from the first two films, but beat-up and charred.

Three minutes into the movie, the spacecraft has been hauled to shore and three generals have arrived at the beach to greet it. Amphibious soldiers in diving suits pop the hatch and help three humanoids dressed in full spacesuits out of the ship and onto dry land as the generals step pompously forward. They salute, and the leader says, “Welcome, gentlemen, to the United St-” And then his voice dies in his throat. The camera cuts back to the astronauts, who have just removed their helmets to reveal three apes, including Cornelius and Zira. The music (tense, but with a psychedelic beat underneath) cuts in as the credits begin. It’s an awesome twist beginning.

Three minutes into the movie, the spacecraft has been hauled to shore and three generals have arrived at the beach to greet it. Amphibious soldiers in diving suits pop the hatch and help three humanoids dressed in full spacesuits out of the ship and onto dry land as the generals step pompously forward. They salute, and the leader says, “Welcome, gentlemen, to the United St-” And then his voice dies in his throat. The camera cuts back to the astronauts, who have just removed their helmets to reveal three apes, including Cornelius and Zira. The music (tense, but with a psychedelic beat underneath) cuts in as the credits begin. It’s an awesome twist beginning.

What we finally learn, as soon as the apes start talking to each other, is that Cornelius, Zira, and their companion Dr. Milo somehow salvaged Taylor’s original ship, repaired it, and launched it before Taylor accidentally blew up the planet. Their escape was so narrow that they witnessed the explosion, and then they followed Taylor’s original trajectory in reverse, taking them back in time to a point several years after Taylor’s initial departure. We are given to understand that Milo is the brains behind their space travel venture (which explains just enough, if you don’t think about it too hard). The three decide to exercise caution in what they reveal to the humans and when, and at first they don’t let anyone know that they can talk. As a result, they are taken to an animal lab for testing and study.

This leads to some humorous scenes where the apes astound the scientists with their intelligence, all the while smirking at each other, but Zira grows impatient with the testing and spills the beans. However, before they can be moved out of the facility, Dr. Milo is tragically killed by a savage gorilla in the next cage, cementing his status as a mere plot device. Everyone is properly saddened and horrified, but he is quickly forgotten as the apes become celebrities in 1970s America, enjoying effectively the opposite of what Taylor had experienced in their society in the first film.

This leads to some humorous scenes where the apes astound the scientists with their intelligence, all the while smirking at each other, but Zira grows impatient with the testing and spills the beans. However, before they can be moved out of the facility, Dr. Milo is tragically killed by a savage gorilla in the next cage, cementing his status as a mere plot device. Everyone is properly saddened and horrified, but he is quickly forgotten as the apes become celebrities in 1970s America, enjoying effectively the opposite of what Taylor had experienced in their society in the first film.

But it isn’t all dinner parties, interviews, and shopping sprees. Dr. Hasslein, the brilliant mind behind the first two human expeditions, is heading a government investigation into these strange beings from the future, and he suspects that there are things Cornelius and Zira aren’t telling. He is, of course, quite right. They do eventually reveal how the earth is destroyed, but they’ve decided not to reveal a great deal about how humans are treated in their society. However, they still say enough to set off alarm bells in Hasslein’s head.

His suspicions are confirmed when he gets Zira drunk and coerces the whole story out of her, on tape, of how she experimented on and even vivisected humans as part of her research. This is the evidence he needs to establish the apes as a clear and present danger to the future of humanity via temporal paradox. See, it turns out that Zira is pregnant, and Hasslein (naturally) assumes that their offspring somehow precipitates the rise of apes and the decline of humanity. He mobilizes the American government to terminate the pregnancy, but the apes manage to escape with the help of Dr. Dixon and Dr. Branton, the first people that befriended them after their arrival.

The two briefly hide out with a circus, where Zira’s baby is born, but they are then forced to flee again. Hasslein and his forces corner them on-board an abandoned ship, and the small family is murdered, husband, wife, and baby. Confirming the death of the young chimp, Hasslein breathes a sigh of relief. However, the audience learns that, unbeknownst to anyone, Zira switched her baby with a newborn chimpanzee from the circus, leaving her own baby with Armando, the circus owner played by Ricardo Montalban. In the film’s final seconds, the baby chimp begins to repeat the word “Mama” over and over again.

The two briefly hide out with a circus, where Zira’s baby is born, but they are then forced to flee again. Hasslein and his forces corner them on-board an abandoned ship, and the small family is murdered, husband, wife, and baby. Confirming the death of the young chimp, Hasslein breathes a sigh of relief. However, the audience learns that, unbeknownst to anyone, Zira switched her baby with a newborn chimpanzee from the circus, leaving her own baby with Armando, the circus owner played by Ricardo Montalban. In the film’s final seconds, the baby chimp begins to repeat the word “Mama” over and over again.

As much of a bummer as the bleak apocalyptic conclusions of the previous two movies are, they can’t really hold a candle to the more localized tragedy of seeing two favorite characters and their baby gunned down in cold blood in order to save humanity, which is ultimately doomed anyway. I don’t believe I’ve ever seen Escape on any lists of great time-travel movies, but that’s what it is, complete with the classic “time cannot be rewritten” theme typical of the more fatalistic examples of the genre.

And yet, despite its stark conclusion, this is easily the most light-hearted of the Apes movies, with far more comedy than any of the other films. It even has an upbeat montage scene! The apes go shopping and dress up in ’70s fashions! There are parties! Reporters follow them everywhere and laugh at their jokes! Perhaps that just makes the ending feel even darker. This is also, in case it wasn’t already apparent, easily the campiest Apes film of the series. And I mean that in the best possible way. Unlike the movie where hideous telepathic mutants wear “pretty human” masks and worship a phallic nuclear bomb, here that’s a feature, not a bug.

The most interesting thing (to me) about the direction this film takes lies in Dr. Hasslein’s response to the apes’ revelations about the future. Although, on the surface, the franchise appears to have toned down its consistently strong anti-nuclear message, it is still very much present in Hasslein’s (and the government’s) insane tunnel vision regarding the apes.

No one in the movie, least of all Dr. Hasslein, ever questions that the apes are from earth’s future, and know what they’re talking about. In fact, Hasslein becomes obsessed with changing the future they describe. But, even though Cornelius reveals that apes rose to dominate men because of humanity’s violent tendencies, and they learn that the planet is eventually destroyed by a nuke, the authorities completely fail to respond to this revelation. Nuclear disarmament is never even mentioned or discussed in any way.These are the “maniacs” that Charlton Heston’s Taylor rails against so memorably at the end of Planet of the Apes. Even when brought face-to-face with the inevitable consequences of nuclear proliferation, it doesn’t even occur to them to act.

Instead, they become fixated on the apes’ experimentation on human subjects in the future in the most absurdly literal way. This aspect of ape society from the first film was always intended as a somewhat heavy-handed critique of human experiments on animals, but in the world of the film this revelation does not prompt any sudden epiphanies about animal cruelty among the humans. On the contrary, it strengthens their resolve to do whatever is necessary to maintain the status quo of human dominion over the earth.

Instead, they become fixated on the apes’ experimentation on human subjects in the future in the most absurdly literal way. This aspect of ape society from the first film was always intended as a somewhat heavy-handed critique of human experiments on animals, but in the world of the film this revelation does not prompt any sudden epiphanies about animal cruelty among the humans. On the contrary, it strengthens their resolve to do whatever is necessary to maintain the status quo of human dominion over the earth.

Speaking of which, this is probably the film’s biggest missed opportunity. The original movie featured an extensive sub-plot in which Cornelius faced a charge of heresy for contradicting the apes’ creationist scriptures with his theory of evolution. It’s hard to imagine that a highly-evolved ape from the future could drop into American society without igniting a very similar religious firestorm. Instead, religion, which features heavily in both of the previous installments, is conspicuously absent from this one.

Of course, even though both the creationist dogma of the apes and the mutants’ veneration of the doomsday bomb are thinly-veiled critiques of religious beliefs, and of religion itself, the veneer of cheesy science-fiction provides just enough distance to avoid obvious offense. But, sci-fi conceit or no, a film set in contemporary America could not hope to deal with religion without raising precisely the same hackles that it would no doubt have been satirizing, which could have spelled a very swift and sudden death for a franchise that was (somehow) regarded by audiences as family entertainment.

So, a bit counter-intuitively, moving the story from a non-human society in the distant future directly into our own backyard somehow ends up making the film’s social critiques feel a bit toothless by comparison to its predecessors. But that doesn’t mean it isn’t, as promised, the hands-down best of the original Ape sequels, and almost worth having suffered through Beneath the Planet of the Apes to get to.

The film begins in 1952, when Lewis is an Oxford don, successful writer, and fairly well-known on both sides of the Atlantic. Joy, a fan of his books, writes a letter asking to meet him when she visits England, and with some trepidation, Lewis (“Jack”) and his brother Warnie arrange a rendezvous over afternoon tea. Jack expects to spend an hour of hopefully not-too-tedious conversation, after which he will never see her again. Instead, he finds himself mysteriously inviting her further and further into his life. He gives her a tour of Oxford, invites her to visit him in his home, and even has her and her son stay for the Christmas holidays.

The film begins in 1952, when Lewis is an Oxford don, successful writer, and fairly well-known on both sides of the Atlantic. Joy, a fan of his books, writes a letter asking to meet him when she visits England, and with some trepidation, Lewis (“Jack”) and his brother Warnie arrange a rendezvous over afternoon tea. Jack expects to spend an hour of hopefully not-too-tedious conversation, after which he will never see her again. Instead, he finds himself mysteriously inviting her further and further into his life. He gives her a tour of Oxford, invites her to visit him in his home, and even has her and her son stay for the Christmas holidays. The film’s opening scenes establish Jack as someone who has very little personal experience in certain areas of life, even though he speaks about them with great authority. Already renowned for his children’s books by this point, one of Jack’s colleagues mockingly asks if he actually knows any children. Jack curtly replies that his brother was a child once, and (“as unlikely as it may seem”) he was, too. In other words, no, he doesn’t know any.

The film’s opening scenes establish Jack as someone who has very little personal experience in certain areas of life, even though he speaks about them with great authority. Already renowned for his children’s books by this point, one of Jack’s colleagues mockingly asks if he actually knows any children. Jack curtly replies that his brother was a child once, and (“as unlikely as it may seem”) he was, too. In other words, no, he doesn’t know any. Finally, addressing the Association of Christian Teachers, Jack gives a signature talk on the problem of pain. He describes a letter he received asking where God was during a national tragedy that occurred the year before. His example is general and impersonal, and his answer to the question is repeated at various points in the movie:

Finally, addressing the Association of Christian Teachers, Jack gives a signature talk on the problem of pain. He describes a letter he received asking where God was during a national tragedy that occurred the year before. His example is general and impersonal, and his answer to the question is repeated at various points in the movie: The first change, of course, is Jack’s acquaintance with Douglas Gresham, who will eventually be his stepson. Initially awkward together, they end up quite close (though their relationship receives little attention in the film). The third happens as Joy weakens and finally passes away. The second, which takes up the bulk of the movie, is Jack’s romantic relationship with Joy, which grows out of an unexpected friendship. Before their relationship can blossom, however, Joy must set about unmasking and piercing the emotional wall that Jack has erected around himself.

The first change, of course, is Jack’s acquaintance with Douglas Gresham, who will eventually be his stepson. Initially awkward together, they end up quite close (though their relationship receives little attention in the film). The third happens as Joy weakens and finally passes away. The second, which takes up the bulk of the movie, is Jack’s romantic relationship with Joy, which grows out of an unexpected friendship. Before their relationship can blossom, however, Joy must set about unmasking and piercing the emotional wall that Jack has erected around himself. Up to this point, the movie could almost be a romantic comedy. Certainly several scenes play out that way, finding humor in the awkwardness Jack and the other stuffy Oxford dons feel when confronted by Joy’s blunt, outspoken nature (which is presented as a distinctly American trait). Cultures clash, opposites attract, sparks fly, etc. Now, the tone shifts dramatically away from comedy. Even Jack’s snarky atheist frenemy, Christopher Riley, stops haranguing him.

Up to this point, the movie could almost be a romantic comedy. Certainly several scenes play out that way, finding humor in the awkwardness Jack and the other stuffy Oxford dons feel when confronted by Joy’s blunt, outspoken nature (which is presented as a distinctly American trait). Cultures clash, opposites attract, sparks fly, etc. Now, the tone shifts dramatically away from comedy. Even Jack’s snarky atheist frenemy, Christopher Riley, stops haranguing him. Nevertheless, Joy recovers, and the couple enjoys a honeymoon in Herefordshire’s Golden Valley. Their destination is inspired by a painting of the valley Jack has had since he was a boy, when he believed it to be a picture of heaven (this is the topic of an early conversation with Joy). As they pause on a walk through the valley to shelter from the rain, Jack expresses how complete his happiness is at that moment, but Joy has a painful reminder:

Nevertheless, Joy recovers, and the couple enjoys a honeymoon in Herefordshire’s Golden Valley. Their destination is inspired by a painting of the valley Jack has had since he was a boy, when he believed it to be a picture of heaven (this is the topic of an early conversation with Joy). As they pause on a walk through the valley to shelter from the rain, Jack expresses how complete his happiness is at that moment, but Joy has a painful reminder: What Joy is suggesting, I think, is a variation on the old idea that only knowing sadness makes it possible to experience true happiness. Or at least that recognizing pleasure as fleeting forces them to appreciate it. Knowing that happiness can’t last is what “makes it real,” a tangible thing that you can be conscious of. However, this is a notion Jack struggles with, particularly once the “pain then” part of “the deal” arrives.

What Joy is suggesting, I think, is a variation on the old idea that only knowing sadness makes it possible to experience true happiness. Or at least that recognizing pleasure as fleeting forces them to appreciate it. Knowing that happiness can’t last is what “makes it real,” a tangible thing that you can be conscious of. However, this is a notion Jack struggles with, particularly once the “pain then” part of “the deal” arrives. All of this culminates in Jack finally going to comfort a grieving Douglas. Talking doesn’t seem to do either of them a lot of good. At last, though, their words are replaced by tears, and they just hold each other and weep. Crying proves to be more cathartic than conversation, and Jack seems to achieve peace over time by letting go of his attempts to explain or understand. In the final scene, we see Jack and Douglas walking together outside on a sunny day as Jack says (in voice-over):

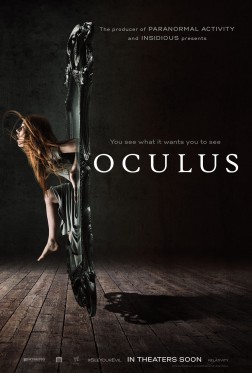

All of this culminates in Jack finally going to comfort a grieving Douglas. Talking doesn’t seem to do either of them a lot of good. At last, though, their words are replaced by tears, and they just hold each other and weep. Crying proves to be more cathartic than conversation, and Jack seems to achieve peace over time by letting go of his attempts to explain or understand. In the final scene, we see Jack and Douglas walking together outside on a sunny day as Jack says (in voice-over): starring Karen Gillan, Brenton Thwaites, Katee Sackhoff, and Rory Cochrane

starring Karen Gillan, Brenton Thwaites, Katee Sackhoff, and Rory Cochrane

Why would a benevolent God allow the suffering of innocents? Why do the wicked prosper? Why do evil and injustice exist if God created everything, and God is good and just? These are the most difficult questions people of faith have to face. “Theodicy” (from the Greek “God” and “justice”) is the word we use to describe attempts to grapple with and answer these questions. The oldest, best-known work of theodicy in the Judeo-Christian tradition is the biblical Book of Job, but many of the most brilliant religious minds in history have also wrestled with these challenges. Theodicy often takes place in the context of philosophical or theological works, but also sometimes in great works of art, including films. This is the third in a series discussing theodicy in movies from various decades, national cinemas, and faith traditions.

Why would a benevolent God allow the suffering of innocents? Why do the wicked prosper? Why do evil and injustice exist if God created everything, and God is good and just? These are the most difficult questions people of faith have to face. “Theodicy” (from the Greek “God” and “justice”) is the word we use to describe attempts to grapple with and answer these questions. The oldest, best-known work of theodicy in the Judeo-Christian tradition is the biblical Book of Job, but many of the most brilliant religious minds in history have also wrestled with these challenges. Theodicy often takes place in the context of philosophical or theological works, but also sometimes in great works of art, including films. This is the third in a series discussing theodicy in movies from various decades, national cinemas, and faith traditions. Higher Ground is based on a 2002 memoir by Carolyn S. Briggs, who also co-wrote the screenplay; a memoir, according to the book’s subtitle, of “Faith Found and Lost.” The book was republished as Higher Ground in order to coincide with the release of the film, but it was originally titled This Dark World. Although the book details the author’s experiences within the world of fundamentalist Christianity, this is not the world referred to by the title. Rather, the author explains, the title is referring to the whole world, a world that is in need of redemption, and it is meant to evoke her own struggles and search for redemption. The phrase comes from Ephesians 6:12: “For our struggle is not against flesh and blood, but against the rulers, against the authorities, against the powers of this dark world […]” (NIV).

Higher Ground is based on a 2002 memoir by Carolyn S. Briggs, who also co-wrote the screenplay; a memoir, according to the book’s subtitle, of “Faith Found and Lost.” The book was republished as Higher Ground in order to coincide with the release of the film, but it was originally titled This Dark World. Although the book details the author’s experiences within the world of fundamentalist Christianity, this is not the world referred to by the title. Rather, the author explains, the title is referring to the whole world, a world that is in need of redemption, and it is meant to evoke her own struggles and search for redemption. The phrase comes from Ephesians 6:12: “For our struggle is not against flesh and blood, but against the rulers, against the authorities, against the powers of this dark world […]” (NIV). Higher Ground begins at a riverside baptism where Corinne, along with several other new believers, is joyously dunked under the water. As she looks up from under the water at the smiling men standing over her, the film flashes back to a very young Corinne, staring up at the camera from underwater as she takes a bath. The movie is divided into “chapters,” the titles of which appear periodically and unobtrusively on the screen as each new section begins. This first portion is called “Summons” (a reference, presumably, to Corinne’s two conversion experiences), and takes us through her childhood and teenage years. As a child, she accepts Jesus during vacation Bible school, but her parents aren’t particularly religious, and her conversion falls by the wayside.

Higher Ground begins at a riverside baptism where Corinne, along with several other new believers, is joyously dunked under the water. As she looks up from under the water at the smiling men standing over her, the film flashes back to a very young Corinne, staring up at the camera from underwater as she takes a bath. The movie is divided into “chapters,” the titles of which appear periodically and unobtrusively on the screen as each new section begins. This first portion is called “Summons” (a reference, presumably, to Corinne’s two conversion experiences), and takes us through her childhood and teenage years. As a child, she accepts Jesus during vacation Bible school, but her parents aren’t particularly religious, and her conversion falls by the wayside. Corinne loves to read and write, and eventually she catches the eye of Ethan Miller, the lead singer in a small-time local rock band, who asks her to write some lyrics for him. Teenage love leads to teenage pregnancy, and Corinne and Ethan get married shortly before their baby is born. Later, they join a small, insular church community of ultra-conservative Christians with an extremely patriarchal hierarchy. Corinne’s sharp mind and natural independence earn her occasional passive-aggressive reprimands from the pastor’s wife, but she accepts them gracefully. She is a believer, and she really wants to get this right. In spite of the restrictiveness of the environment, the relationships are warm and genuine.

Corinne loves to read and write, and eventually she catches the eye of Ethan Miller, the lead singer in a small-time local rock band, who asks her to write some lyrics for him. Teenage love leads to teenage pregnancy, and Corinne and Ethan get married shortly before their baby is born. Later, they join a small, insular church community of ultra-conservative Christians with an extremely patriarchal hierarchy. Corinne’s sharp mind and natural independence earn her occasional passive-aggressive reprimands from the pastor’s wife, but she accepts them gracefully. She is a believer, and she really wants to get this right. In spite of the restrictiveness of the environment, the relationships are warm and genuine. It’s not clear that Corinne is particularly aware, at least as a child, of how deeply the miscarriage affects her life. She is certainly conscious of the deep sadness of the event, and of the disintegration of her parents’ marriage, but perhaps not of how they are connected. As a child, this tragedy does not lead her to harbor any doubts or ask any questions, particularly as she seems to have no larger, guiding worldview to question.

It’s not clear that Corinne is particularly aware, at least as a child, of how deeply the miscarriage affects her life. She is certainly conscious of the deep sadness of the event, and of the disintegration of her parents’ marriage, but perhaps not of how they are connected. As a child, this tragedy does not lead her to harbor any doubts or ask any questions, particularly as she seems to have no larger, guiding worldview to question. Several tense moments pass, and it seems certain that this will not end well, but then Ethan finds the baby. The next scene shows the small family huddled together in bed, relieved to be alive, as Ethan comes to a realization: God saved them. God is real, and this was a sign from Him. Ethan randomly flips open a Bible (“to see what God wants to tell us”) and lands on a passage about dashing infants against the rocks. The couple share a horrified look, and a glance at their baby, then decide they might be better off starting at the beginning of the Bible.

Several tense moments pass, and it seems certain that this will not end well, but then Ethan finds the baby. The next scene shows the small family huddled together in bed, relieved to be alive, as Ethan comes to a realization: God saved them. God is real, and this was a sign from Him. Ethan randomly flips open a Bible (“to see what God wants to tell us”) and lands on a passage about dashing infants against the rocks. The couple share a horrified look, and a glance at their baby, then decide they might be better off starting at the beginning of the Bible. Much of this section revolves around Corinne’s friendship with Annika, another church member. Annika seems very different from the other women in the church. She is a devout believer, but she and Corinne also share an irreverent sense of humor. While the rest of the women gather around the refreshment table following a Bible study led by the pastor’s wife, Annika tells Corinne, “I know Deborah loves the Lord, and she means well, but her sermons are starting to make me feel suicidal.” A few seconds later, Deborah invites the women to come try the carob brownies. “You know what carob tastes like?” Corinne quietly asks Annika. “Disappointment.”

Much of this section revolves around Corinne’s friendship with Annika, another church member. Annika seems very different from the other women in the church. She is a devout believer, but she and Corinne also share an irreverent sense of humor. While the rest of the women gather around the refreshment table following a Bible study led by the pastor’s wife, Annika tells Corinne, “I know Deborah loves the Lord, and she means well, but her sermons are starting to make me feel suicidal.” A few seconds later, Deborah invites the women to come try the carob brownies. “You know what carob tastes like?” Corinne quietly asks Annika. “Disappointment.” Plus, Annika speaks in tongues, which the rest of the church regards with a fair amount of suspicion (Corinne’s husband opines that “it’s probably voodoo”), though Corinne is jealous: “I want it. You get everything! You do! I want it.” All-in-all, it seems that the rest of the church might look askance at much of Annika’s behavior, but this only seems to make the two women better friends. Annika is Corinne’s confidant, giving her (bizarre) advice on spicing up her sex life and, later, catering to her cravings and massaging her feet while she is pregnant.

Plus, Annika speaks in tongues, which the rest of the church regards with a fair amount of suspicion (Corinne’s husband opines that “it’s probably voodoo”), though Corinne is jealous: “I want it. You get everything! You do! I want it.” All-in-all, it seems that the rest of the church might look askance at much of Annika’s behavior, but this only seems to make the two women better friends. Annika is Corinne’s confidant, giving her (bizarre) advice on spicing up her sex life and, later, catering to her cravings and massaging her feet while she is pregnant. This revelation precedes perhaps the most devastating scene in the film, during the church service following Annika’s recovery. The camera pans right across the front row of the congregation as Pastor Bill says, “Our God is the God who delivers. And He has delivered our sister from the shadow of the valley of death, and so we thank God tonight! We rejoice with Ned, and Annika, and their beautiful kids.” As the camera crosses the center aisle, we see Annika, slumped over in a wheelchair, her face slack and eyes dull as she stares blankly ahead at nothing.

This revelation precedes perhaps the most devastating scene in the film, during the church service following Annika’s recovery. The camera pans right across the front row of the congregation as Pastor Bill says, “Our God is the God who delivers. And He has delivered our sister from the shadow of the valley of death, and so we thank God tonight! We rejoice with Ned, and Annika, and their beautiful kids.” As the camera crosses the center aisle, we see Annika, slumped over in a wheelchair, her face slack and eyes dull as she stares blankly ahead at nothing. This is the beginning of the end of Corinne’s involvement in the church. The next scene begins a new chapter: “Wrestling Until Dawn;” words that evoke Jacob’s struggle with God throughout the night in Genesis 32. For the next half-hour of the movie, Corinne’s marriage and her faith slowly unravel. She leaves her husband, and the church, and begins a journey of self-discovery that she had left behind as a teenager, leading to her final “confession” to her former church.

This is the beginning of the end of Corinne’s involvement in the church. The next scene begins a new chapter: “Wrestling Until Dawn;” words that evoke Jacob’s struggle with God throughout the night in Genesis 32. For the next half-hour of the movie, Corinne’s marriage and her faith slowly unravel. She leaves her husband, and the church, and begins a journey of self-discovery that she had left behind as a teenager, leading to her final “confession” to her former church. After Corinne turns the microphone back over to Pastor Bill, he leads the congregation in the hymn “How Great Thou Art” as she walks to the back of the church and opens the door to leave. But she stops in the doorway and looks back, and then she turns and rests her forehead against the door as she holds it with her hand, and closes her eyes and sways slightly with the music. And then she turns back again to look inside, and her weight shifts ever so slightly, but before we can tell whether she is about to step outside or inside, the movie ends.

After Corinne turns the microphone back over to Pastor Bill, he leads the congregation in the hymn “How Great Thou Art” as she walks to the back of the church and opens the door to leave. But she stops in the doorway and looks back, and then she turns and rests her forehead against the door as she holds it with her hand, and closes her eyes and sways slightly with the music. And then she turns back again to look inside, and her weight shifts ever so slightly, but before we can tell whether she is about to step outside or inside, the movie ends.

It certainly seems likely that these two films will continue to do quite well by Christian Movie standards. And yet, Son of God currently has a very poor

It certainly seems likely that these two films will continue to do quite well by Christian Movie standards. And yet, Son of God currently has a very poor  And even if it is, why is there even a market for one more straightforward retelling of the life of Christ? By my count there have been as many as 10 films about all or part of Jesus’s life in the last fifteen years alone. There are many more stretching back even further. One of the oldest surviving feature films in existence,

And even if it is, why is there even a market for one more straightforward retelling of the life of Christ? By my count there have been as many as 10 films about all or part of Jesus’s life in the last fifteen years alone. There are many more stretching back even further. One of the oldest surviving feature films in existence,  Then there’s God’s Not Dead, a movie which draws its title from a popular “Christian rock” song by the “Newsboys,” and its plot from

Then there’s God’s Not Dead, a movie which draws its title from a popular “Christian rock” song by the “Newsboys,” and its plot from  Noah, on the other hand, is doing quite well critically, if the few dozen early reviews are to be trusted. However, though it may very well make more money than both of the other movies combined (in fact, it will have to, by a healthy margin, if it wants to recoup its budget), Noah will likely be seeing very poor attendance from the niche audience of American evangelicals that the other films are marketed to. This despite the fact that they ought to be the most interested in seeing the first big-budget Bible epic in years (decades?), a movie made by a critically-acclaimed director, and with the potential to start meaningful conversations about matters of faith. Something is terribly wrong.

Noah, on the other hand, is doing quite well critically, if the few dozen early reviews are to be trusted. However, though it may very well make more money than both of the other movies combined (in fact, it will have to, by a healthy margin, if it wants to recoup its budget), Noah will likely be seeing very poor attendance from the niche audience of American evangelicals that the other films are marketed to. This despite the fact that they ought to be the most interested in seeing the first big-budget Bible epic in years (decades?), a movie made by a critically-acclaimed director, and with the potential to start meaningful conversations about matters of faith. Something is terribly wrong. What do glimpses of the kingdom of heaven look like on film? Surely not a shallow, low-budget production with a thinly-disguised message that an American church can build a 6-week Bible study around. I can’t help but think here of

What do glimpses of the kingdom of heaven look like on film? Surely not a shallow, low-budget production with a thinly-disguised message that an American church can build a 6-week Bible study around. I can’t help but think here of

Images of “thriving in God’s good world” are everywhere in

Images of “thriving in God’s good world” are everywhere in

The film cuts to Ponette riding in the car with her father, on their way to stay with her young cousins, Matiaz and Delphine. Her father is upset. He rages about her mother’s stupidity and carelessness for being in a car accident. Ponette defends her. Finally they stop and get out of the car. Ponette’s father carries her on his shoulders and makes her promise that she will never die. Then he tells her that her mother is dead. In that moment, her entire world crumbles around her, and she will spend the rest of the movie trying to put it back together.

The film cuts to Ponette riding in the car with her father, on their way to stay with her young cousins, Matiaz and Delphine. Her father is upset. He rages about her mother’s stupidity and carelessness for being in a car accident. Ponette defends her. Finally they stop and get out of the car. Ponette’s father carries her on his shoulders and makes her promise that she will never die. Then he tells her that her mother is dead. In that moment, her entire world crumbles around her, and she will spend the rest of the movie trying to put it back together. Naturally, the one thing she takes from all this is that she should go sit and wait for this to happen. She spends the better part of a few days parked in the same spot outside before her aunt realizes what she is doing: “I’m sorry. […] You shouldn’t wait. She won’t come. Jesus came back, but when other people die, they don’t really come back. She hears you, sees you, and she still loves you. But she can’t come back. I’m sure of it.” Ponette is not convinced. Maybe her mother won’t come back because no one else wants her to come back.

Naturally, the one thing she takes from all this is that she should go sit and wait for this to happen. She spends the better part of a few days parked in the same spot outside before her aunt realizes what she is doing: “I’m sorry. […] You shouldn’t wait. She won’t come. Jesus came back, but when other people die, they don’t really come back. She hears you, sees you, and she still loves you. But she can’t come back. I’m sure of it.” Ponette is not convinced. Maybe her mother won’t come back because no one else wants her to come back. Noticing that she is still sad and withdrawn, Ponette’s older, world-wise cousin, Delphine (who is perhaps 6), tells her she should talk to Ada. Ada is the only Jewish girl at the school, and being Jewish, she is a “Child of God,” and may wield some special influence with the Big Man Upstairs. Ada confirms this, and offers to put Ponette through the same trials she underwent in order to become a Child of God. Ponette readily agrees, and is subjected to a battery of playground tests.

Noticing that she is still sad and withdrawn, Ponette’s older, world-wise cousin, Delphine (who is perhaps 6), tells her she should talk to Ada. Ada is the only Jewish girl at the school, and being Jewish, she is a “Child of God,” and may wield some special influence with the Big Man Upstairs. Ada confirms this, and offers to put Ponette through the same trials she underwent in order to become a Child of God. Ponette readily agrees, and is subjected to a battery of playground tests. Young children do not tend to sit still and talk, and Ponette is in constant motion, even while in conversation. When her father sets her down on the hood of their car and informs her that her mother is dead, even as she begins to cry she is distractedly climbing up to the roof of the car and sliding down the windshield over and over. Her conversations with Ada about becoming a Child of God take place as she follows the other girl around the playground: walking, jogging, climbing, jumping. She asks her friends why God will not send her a sign while they stand at the sink together brushing their teeth. This seems so natural, and is shot so brilliantly, that it isn’t even noticeable until you start to think about it.

Young children do not tend to sit still and talk, and Ponette is in constant motion, even while in conversation. When her father sets her down on the hood of their car and informs her that her mother is dead, even as she begins to cry she is distractedly climbing up to the roof of the car and sliding down the windshield over and over. Her conversations with Ada about becoming a Child of God take place as she follows the other girl around the playground: walking, jogging, climbing, jumping. She asks her friends why God will not send her a sign while they stand at the sink together brushing their teeth. This seems so natural, and is shot so brilliantly, that it isn’t even noticeable until you start to think about it. This time, when her mother says goodbye, Ponette knows that she will not see her again. This is clearly a struggle, but she goes on to meet her father, who has been waiting to pick her up. No one seems to have missed her, though she has clearly been gone all day, and contrary to his earlier impatience, her father calmly accepts her story about going to the cemetery alone and spending the day talking to her mother. As they drive off together, Ponette seems happy for the first time, smiling directly into the camera for a brief moment before the car pulls away.

This time, when her mother says goodbye, Ponette knows that she will not see her again. This is clearly a struggle, but she goes on to meet her father, who has been waiting to pick her up. No one seems to have missed her, though she has clearly been gone all day, and contrary to his earlier impatience, her father calmly accepts her story about going to the cemetery alone and spending the day talking to her mother. As they drive off together, Ponette seems happy for the first time, smiling directly into the camera for a brief moment before the car pulls away. She “imagines” it, though I think that’s a clumsy, simplistic way of describing what’s going on in her head in these scenes. There are none of the signifiers that we are conditioned to expect when a movie presents us with a dream sequence or a fantasy, because this is all from Ponette’s point-of-view, and her young mind doesn’t draw a distinction between fantasy and reality. It is all of a piece with the way writer-director Jacques Doillon flawlessly captures the inner life of childhood.

She “imagines” it, though I think that’s a clumsy, simplistic way of describing what’s going on in her head in these scenes. There are none of the signifiers that we are conditioned to expect when a movie presents us with a dream sequence or a fantasy, because this is all from Ponette’s point-of-view, and her young mind doesn’t draw a distinction between fantasy and reality. It is all of a piece with the way writer-director Jacques Doillon flawlessly captures the inner life of childhood. Hopefully, as part of that healing, Ponette can also come to understand, not that God was indifferent to her pain, but that His love and attention were not conditional upon a legalistic model of doing just the right thing to be worthy. She did not need to recite magic words, or undertake a series of playground trials, or fold her hands just so while praying (as she shows Matiaz in one scene). Only when she has utterly exhausted her efforts to insert precisely the correct change into the Deus Ex Machina can something transcendent take place. Maybe she will learn that way, after all.

Hopefully, as part of that healing, Ponette can also come to understand, not that God was indifferent to her pain, but that His love and attention were not conditional upon a legalistic model of doing just the right thing to be worthy. She did not need to recite magic words, or undertake a series of playground trials, or fold her hands just so while praying (as she shows Matiaz in one scene). Only when she has utterly exhausted her efforts to insert precisely the correct change into the Deus Ex Machina can something transcendent take place. Maybe she will learn that way, after all.

Kichijiro brings them to a village of Christians who have continued practicing their faith in secret, albeit without the benefit of a priest to perform the sacraments. Unable to search openly for Ferreira, they take up the work of ministering to the villagers. Meanwhile, Kichijiro begins bragging about his role in smuggling two Jesuits into Japan. As word spreads, Christians from other villages come looking for the priests, and it seems only a matter of time before the authorities are alerted.

Kichijiro brings them to a village of Christians who have continued practicing their faith in secret, albeit without the benefit of a priest to perform the sacraments. Unable to search openly for Ferreira, they take up the work of ministering to the villagers. Meanwhile, Kichijiro begins bragging about his role in smuggling two Jesuits into Japan. As word spreads, Christians from other villages come looking for the priests, and it seems only a matter of time before the authorities are alerted. But the Japanese authorities don’t need another Christian martyr. They need an apostate missionary to symbolize their victory and demoralize the remaining Japanese believers. Rodrigues cannot hope for a noble death, only an ignoble existence in which he clings to his beliefs while other Christians are forced to die for them. Initially disgusted by Ferreira’s “betrayal” of the faith, he slowly begins to understand the impossible choice Ferreira was given.

But the Japanese authorities don’t need another Christian martyr. They need an apostate missionary to symbolize their victory and demoralize the remaining Japanese believers. Rodrigues cannot hope for a noble death, only an ignoble existence in which he clings to his beliefs while other Christians are forced to die for them. Initially disgusted by Ferreira’s “betrayal” of the faith, he slowly begins to understand the impossible choice Ferreira was given. Having lost a second chance at redemption, Kichijiro follows pathetically after the fugitive Father Rodrigues, begging for forgiveness and absolution even up to the moment Rodrigues is taken by the soldiers. As the priest is hauled off, Kichijiro remains prostrate on the beach, weeping with his face buried in the sand, while the captain of the guard dumps his payment over him. Still hoping to be absolved, he trails desperately after the group, breaking into the prison to beg Rodrigues again to hear his confession and forgive him. When the guards come to kick him out, he tells them he is a Christian and demands to be locked up, and they oblige.

Having lost a second chance at redemption, Kichijiro follows pathetically after the fugitive Father Rodrigues, begging for forgiveness and absolution even up to the moment Rodrigues is taken by the soldiers. As the priest is hauled off, Kichijiro remains prostrate on the beach, weeping with his face buried in the sand, while the captain of the guard dumps his payment over him. Still hoping to be absolved, he trails desperately after the group, breaking into the prison to beg Rodrigues again to hear his confession and forgive him. When the guards come to kick him out, he tells them he is a Christian and demands to be locked up, and they oblige.

What does God’s silence mean in this story? Was God truly silent? Ferreira and Rodrigues both certainly knew Jesus’ words in John 15:13, “Greater love has no one than this, that someone lay down his life for his friends.” Through Rodrigues’ painful journey to apostasy, Shūsaku Endō suggests a different meaning to those words; one that is much more difficult to understand.

What does God’s silence mean in this story? Was God truly silent? Ferreira and Rodrigues both certainly knew Jesus’ words in John 15:13, “Greater love has no one than this, that someone lay down his life for his friends.” Through Rodrigues’ painful journey to apostasy, Shūsaku Endō suggests a different meaning to those words; one that is much more difficult to understand.