Film History Essentials: New Brooklyn to New York via Brooklyn Bridge, No. 1 (1899)

For most of the 19th century, travel between Brooklyn and New York City (now the borough of Manhattan) was limited to the various ferry lines that crossed the East River. The proposal for the first bridge between the two was approved shortly after the Civil War, but it was not completed and opened to the public for 16 years. For 20 years after its completion, the Brooklyn Bridge was the largest suspension bridge in the world, with a length of over 6,000 feet (and 1595 feet for its longest span).

The structure was a marvel of engineering, but all the more so considering the circumstances of its construction. The company responsible for building the bridge was actually overseen by the notoriously-corrupt Tammany Hall political machine. At least one contractor, for the all-important cables, enriched themselves by using inferior materials.

By the end, the bridge cost the modern equivalent of over $400 million (though notorious conman George C. Parker “sold” it a number of times for a fraction of that cost). However, it proved even costlier to some of those who worked on it. Some 27 people died during the bridge’s construction, and many more suffered debilitating injuries, including some of those in charge of the project.

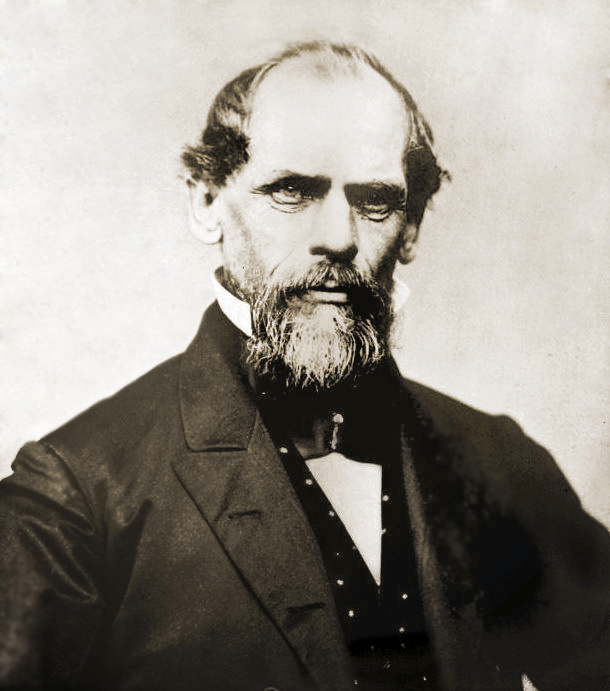

John Roebling (see right), a German immigrant who had experience designing and constructing suspension bridges, was appointed as the project’s chief engineer in 1867. Two years later, he was working on-site, standing at the edge of a dock, when his foot was crushed by an arriving ferry. He had to have his toes amputated, and then he contracted tetanus and died only a few weeks later. He was replaced by his 32-year old son, Washington.

Washington had worked with his father since the 1850s, and had also aided with the construction of suspension bridges as an officer in the Union artillery during the Civil War. He attained the rank of brevet colonel by war’s end, having served with some distinction. Among other things, he performed reconnaissance from a hot-air balloon, and saw action at several major battles, including Gettysburg.

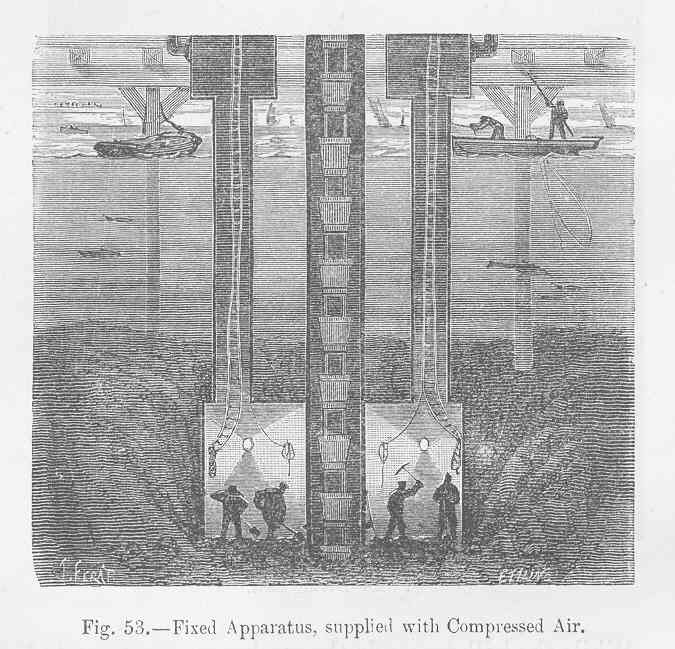

After taking over the Brooklyn Bridge project, Washington designed two pneumatic caissons (see left) that would allow the foundations for the bridge’s two main towers to be built underwater. These large, bottomless boxes were sunk down into the river mud and filled with pressurized air so workers could descend, clear the debris, and pour concrete. The use of these caissons was still a relatively recent innovation, and with them came a new danger that was not yet well-understood: decompression sickness, or (as it was originally known to bridge-builders) caisson disease.

Frank Harris, an Irish immigrant who worked on the bridge as a teenager, gives this first-hand account of the conditions:

In the bare shed where we got ready, the men told me no one could do the work for long without getting the ‘bends’; the ‘bends’ were a sort of convulsive fit that twisted one’s body like a knot and often made you an invalid for life. […] ‘If they’d pump in good air, it would be O.K; but that would cost a little time and trouble, and men’s lives are cheaper.’ […]

When we went into the ‘air-lock’ and they turned on one air-lock after another of compressed air, the men put their hands to their ears and I soon imitated them, for the pain was very acute. Indeed, the drums of the ears are often driven in and burst if the compressed air is brought in too quickly.

[…]

When the air was fully compressed, the door of the air-lock opened at a touch and we all went down to work with pick and shovel on the gravelly bottom. My headache soon became acute. The six of us were working naked to the waist in a small iron chamber with a temperature of about 80 degrees Fahrenheit: in five minutes the sweat was pouring from us, and all the while we were standing in icy water that was only kept from rising by the terrific air pressure.

[…]

After two hours’ work down below we went up into the air-lock room to get gradually ‘decompressed,’ […] I was soon as cold as wet rat and felt depressed and weak to boot […] I took a cupful of hot cocoa with Anderson, which stopped the shivering, and I was soon able to face the afternoon’s ordeal.For three or four days things went fairly well with me, but on the fifth day or sixth we came on a spring of water, or ‘gusher,’ and were wet to the waist before the air pressure could be increased to cope with it. As a consequence, a dreadful pain shot through both my ears: I put my hands to them tight and sat still for little while.

[…]

One day, just as the ‘decompression’ of an hour and a half was ending, an Italian named Manfredi fell down and writhed about, knocking his face on the floor till the blood spurted from his nose and mouth. When we got him into the shed, his legs were twisted like plaited hair. The surgeon had him taken to the hospital. I made up my mind that a month would be enough for me.

In 1872, Washington Roebling came back up too quickly after several hours working in the caisson and immediately fell unconscious. Lucky to survive, his mistake reportedly destroyed his health and left him bedridden for life. From that point forward, he supervised the construction of the bridge from home, observing the progress of the construction via telescope. His wife, Emily Warren Roebling, then 29, carried messages from Washington to the on-site engineers, but she did so much more than that.

Emily taught herself the necessary mathematics, specifications, knowledge of materials, and a dozen other intricacies necessary to take on the in-person, day-to-day duties of supervising the project as its chief engineer for the next 11 years. When the bridge was officially opened, on 24 May 1883, Emily was the first to cross it. She had been indispensable to the design and completion of one of the great feats of 19th century engineering at a time when women were largely barred from formal education and employment in engineering fields.

During her years working on the Brooklyn Bridge, the first engineering degrees were awarded to American women from a few institutions. Still, most universities would not award degrees to women who met the requirements, even when they excelled, providing them instead with a certificate of proficiency or completion. Edith Clarke, the first American woman to be employed as an engineer (in 1922) was born three months before the bridge was completed.

The ride seen in New Brooklyn to New York via Brooklyn Bridge, No. 1 was filmed on 22 September 1899, 16 years after the bridge was completed. It was also a year and a half after Brooklyn became a part of New York City through the consolidation that created the five boroughs that exist today. The film was produced for Edison’s company by James White. As the title implies, this was one of a pair of films. In fact, these were just a few of a number of Brooklyn Bridge films from around this time, which include a fantastic panorama taken from the bridge’s tower by American Mutoscope.

The title implies a few significant things about the film. First, “New” at the front of the title suggests that there was a previous version, and this is an updated remake. This was usually done when an earlier print wore out, but may have also been a showcase for recent changes to the bridge crossing. The trolley tracks were a fairly recent addition to the bridge, built in 1898. Trolley service across the bridge continued until 1950.

The title also seems to indicate that this is a crossing from Brooklyn over to Manhattan, but in fact it is the reverse. The ride begins in Manhattan and ends in Brooklyn (as can be seen in the photo below, taken from the Brooklyn side). The film New Brooklyn to New York via Brooklyn Bridge, no. 2, presumably taken immediately after, depicts the return trip.

Screening:

After a few badly-deteriorated frames and a sudden cut, the film begins with a very cool shot from within the covered station, which frames a view of the nearest bridge tower. More and more of the outside comes into view as the camera emerges into the daylight to include the surrounding city in the shot, as well. What immediately stands out is the amount and variety of traffic crossing the bridge alongside the trolley.

The pedestrian lane of the bridge seems quite crowded, particularly considering that it’s a weekday and the bridge is over a mile long. Nevertheless, tens of thousands of people were crossing the bridge on foot each week, and it may be worth noting that at this time, walking across the bridge was free, whereas passengers and carriages had to pay a toll. A roughly equal-sized crowd visible on the bridge’s other side suggests that there are at least several hundred pedestrians crossing at this time.

There are also some people visible on the tracks, though it isn’t clear why. A man strides across in front of the approaching car at just under a minute in. A few seconds later, there are three men visible pressing themselves against the right-hand side as the trolley passes by. Just before the car reaches the section of track where people can be seen looking down and crossing over above, another man is approaching along the narrow walkway. He, too, presses himself against the side as the trolley goes by.

Two lanes of traffic are visible on the outer edge to each side of the bridge. The outermost is for wagons and carriages, while the lane adjacent to the trolley tracks is for cable cars. There are a surprising number of cable cars in operation at the same time. At least six are visible coming towards the near end of the bridge on the left side before the view from the trolley no longer includes that lane.

Only two are visible going the other way alongside the trolley at first, but it is possible to see the shadow of each cable car running alongside (cast onto the tracks) the whole way across. The trolley, which is clearly the fastest way to cross, passes about 10 cable cars (about one every 10 seconds), and they seem to be roughly evenly-spaced. The few that are actually visible are full of passengers, as well.

Finally, a number of billboards are visible along the way. The first, which adorns a building immediately after the trolley comes out of the station, is for Franco-American Soups. This brand, founded in Jersey City by a French immigrant, was bought out by the Campbell Soup Company in 1915, but still exists on a few Campbell products today. There are also billboards for Quaker Oats, a company that was only about 20 years old in 1899, on opposite sides of the far end of the bridge.

There are several other signs that can be partially read, but are harder to identify definitively. Some of these are more clearly visible in the photograph above. However, there is one more that is legible in the film, right at the final bend: “TAKE BROOKLYN ELEVATED R.R./SHORTEST & QUICKEST ROUTE TO/CONEY ISLAND/EXCURSION TICKETS 20¢.” 20 cents in 1899 is the equivalent of over $7 today.

The trolley pulls into the other station after about two minutes, suggesting an average speed of around 30 miles per hour. As it comes to a stop, a train departs from the opposite side of the platform for a destination further down the line in Brooklyn. This film provides a fascinating and visually-arresting glimpse into life in turn-of-the-century New York, when much that is now very old was still quite new.

You can read about this nitrate film’s rediscovery in 1981 and later digitization here: https://time.com/5280029/brooklyn-bridge-early-film-rediscovered/

They also include a link to the LoC paper print copy, which includes the first couple of seconds missing from the nitrate.

LikeLike