Film History Essentials: L’Affaire Dreyfus (1899)

(English: The Dreyfus Affair)

In 1859, Alfred Dreyfus (see below) was born to a successful Jewish textile merchant in Alsace, a region on the far eastern edge of France. Bordering Germanic states to the north and west and Switzerland to the south, Alsace was also historically Germanic, but had been conquered by France in the 1600s. Because of its history and geographic position, it developed a unique blend of French and Germanic culture.

In 1871, when Dreyfus was 11 years old, the Franco-Prussian War ended with the fall of Paris, and the new German Empire annexed the territory of Alsace-Lorraine from France. Given the choice between becoming German citizens and leaving their homes, Dreyfus and his family left and eventually settled in Paris. Just after his 18th birthday, Dreyfus enrolled in a military academy.

During the next 15 years, he advanced rapidly as an artillery officer. He was promoted, first to lieutenant, and then to captain, and was admitted into the French military’s most elite war college. Upon graduation, he was assigned to the French Army’s General Staff Headquarters. By now he was also married and was the father of two children. But not everything was going smoothly.

In the fall of 1894, public life in France was extremely volatile, rife with deep divisions. A series of crises involving warring factions and corruption scandals resulted in tremendous government instability, with no one party definitively holding power, which remained tenuously balanced and was subject to dramatic shifts. In addition, the French President, Sadi Carnot, was assassinated that June, stabbed to death by an Italian anarchist in an act of revenge for the execution of two anarchist bombers.

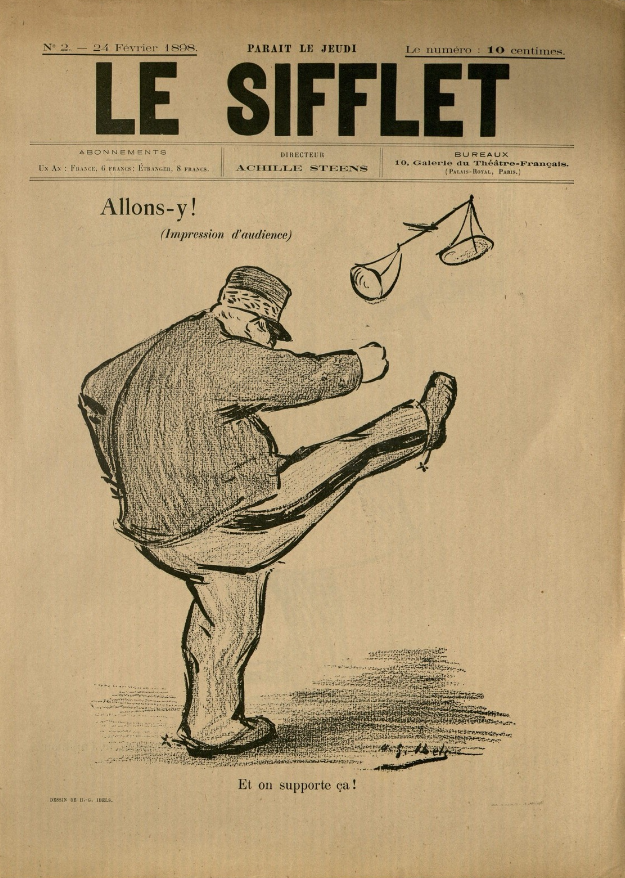

Further, just a few years before, the Republic narrowly avoided a coup by the supporters of the revanchist, proto-fascist General Boulanger. Although Boulanger committed suicide in exile in 1891, the vengeful, ultra-nationalist spirit he represented remained popular, especially in the French military. The sting of defeat in 1871, and particularly of the lost territory, still lingered (see above). France was caught in an expensive arms race with Germany over the development of new artillery, and paranoia regarding potential espionage was rampant.

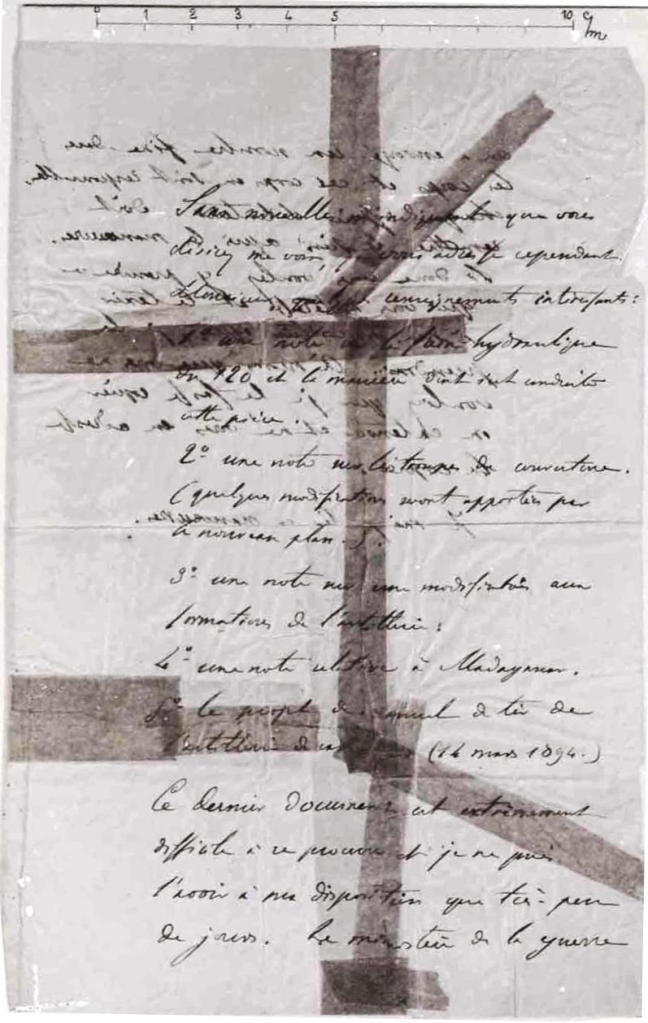

In the midst of all this, three months after the assassination, a French housekeeper, working as a spy in the German Embassy, found several torn scraps of paper (see right) that referred to the imminent transfer of classified information about a newly-developed artillery piece. This was proof of a leak that many had already suspected. and almost immediately, suspicion fell on Alfred Dreyfus. He spoke fluent German due to his Alsatian origins, he was an artillery officer, and, as the only Jewish officer on the General Staff, he was regarded as a bit of an outsider.

There was never any real evidence, or even any strong reason to believe that Dreyfus was a spy. However, these and a dozen other pieces of nonsensical reasoning that amounted to nothing were all aligned against him. The note, the only piece of physical evidence connected with the case at all, was not found to match Dreyfus’s handwriting, but the authorities simply claimed that he had deliberately disguised his writing.

The Minister of War, General Auguste Mercier (see left), eager for a high-profile success after recent embarrassments, was utterly convinced of Dreyfus’s guilt. He and the head of his investigation, a Major Armand du Paty de Clam, tried to trick Dreyfus into confessing, and when that failed, du Paty de Clam suggested that Dreyfus take the “honorable” way out and commit suicide. When neither tactic succeeded, Mercier was forced to take the complete lack of a case to trial. Even the indictment was a sham, pointing to the lack of physical evidence in the case as further proof of Dreyfus’s guilt, showing his cleverness at covering his tracks.

Military leaders engaged in significant manipulation of public opinion before the trial through the anti-Semitic press. When acquittal still seemed possible after the complete emptiness of their case was revealed, officials compiled a “secret dossier” of fabricated evidence, and, by order of Mercier, illegally submitted it to the judges during deliberations in order to sway their ruling. Throughout the affair, various authorities seem to have been motivated by both unwavering certainty of Dreyfus’s guilt in the face of any and all evidence to the contrary, and the total refusal to acknowledge or redress any wrong when doing so would indicate publicly that the military was fallible.

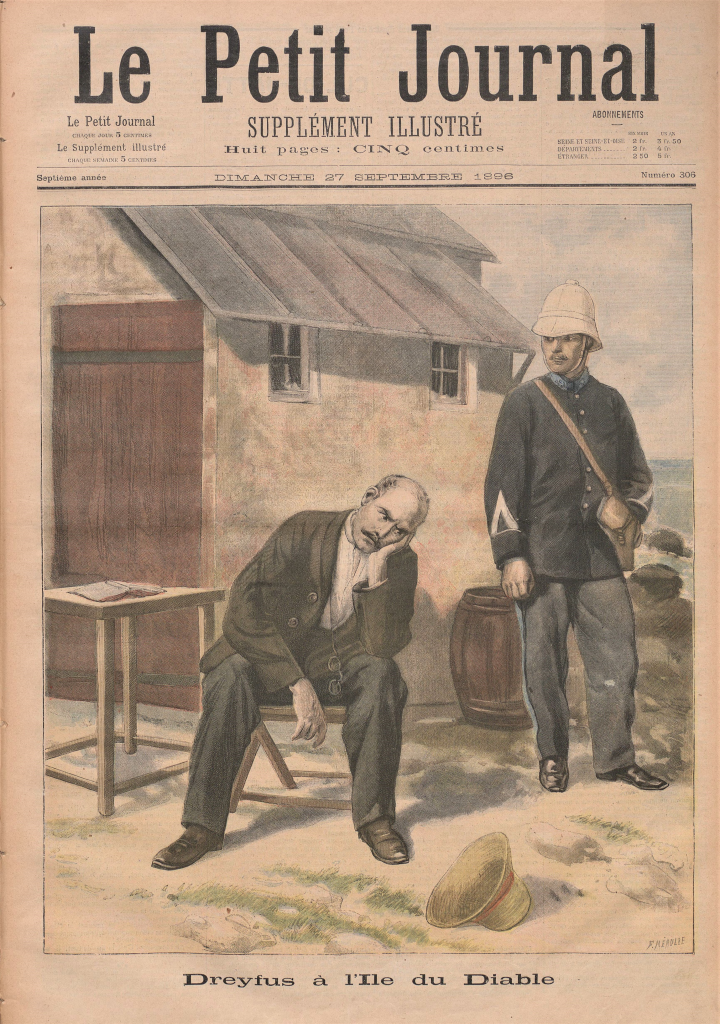

Ultimately, Dreyfus was found guilty and sentenced to permanent imprisonment in exile. He was subjected to military degradation (see right), and then deported to Devil’s Island, off the coast of French Guiana, in the spring of 1895. He was the only prisoner on the tiny, 35-acre island. He was housed in a small stone hut where he would spend the next four years. Beginning in 1896, he was forced to remain in the hut’s bed with his ankles shackled together.

(Incidentally, the guards began chaining Dreyfus after a false story claimed that he had escaped. The story was actually planted in a British newspaper by Alfred’s older brother Mathieu, a fervent champion of his cause who was looking for ways to keep his brother’s story alive in the public eye. The ploy worked, but obviously it also had an unintended consequence.)

Dreyfus believed himself to be doomed and forgotten. He had no idea that, back in France, his conviction was slowly developing into a massive scandal that would consume the nation. That summer (1895), Major Georges Picquart (see left) became the new head of military counter-intelligence. Discovering that the leaks had continued despite Dreyfus’s absence, Picquart investigated further.

Within several months, he had uncovered the real culprit, a Major Ferdinand Esterhazy, as well as evidence of the conspiracy against Dreyfus. However, Picquart underestimated his superiors’ commitment to maintaining the façade they had created. He was also unaware that his own deputy, Major Hubert-Joseph Henry, was actively working against him, continuing to fabricate evidence against Dreyfus and tipping off Esterhazy (who was Henry’s friend).

The result was that Picquart was transferred out of the country. When that didn’t silence him, he was eventually imprisoned. But by now there was enough public scrutiny that Esterhazy was put on trial at the beginning of 1898. The proceedings were every bit as farcical as the Dreyfus trial, and Esterhazy was soon acquitted in a further effort to protect the conviction of Dreyfus. To be clear: The French military actively protected a known spy and traitor in order to avoid publicly admitting that they had falsely imprisoned a loyal soldier.

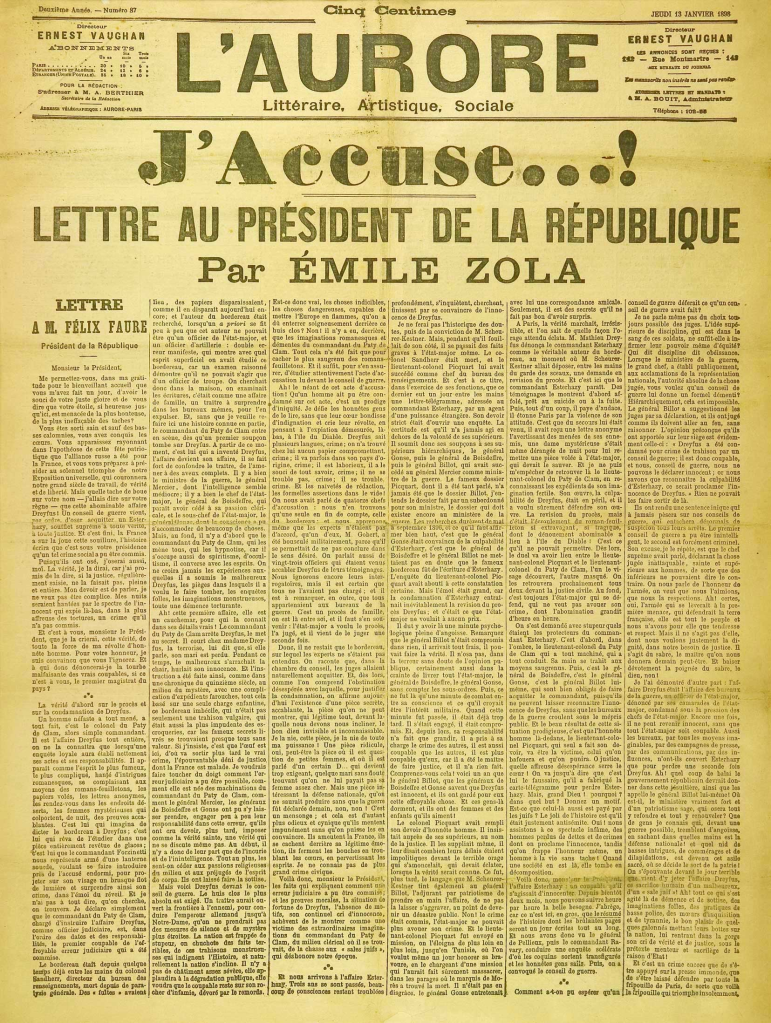

Two days after Esterhazy’s acquittal, the newspaper L’Aurore published an open letter by the celebrated novelist Émile Zola under the famous headline “J’Accuse…!” (see right). Zola’s outpouring of outrage at the ongoing miscarriages of justice were a rallying cry for supporters of Dreyfus and of the rule of law in France, and his words drew international attention. Still, the battle was far from over.

Zola was put on trial for libel, and once again the outcome was a foregone conclusion. He was convicted and sentenced to a year in prison, but fled to England, where he continued to write about “The Affair.” Meanwhile, things were beginning to unravel for the conspirators. The public was inflamed, on both sides, and anti-Semitic riots broke out with each new development and revelation.

Godefroy Cavaignac, the new Minister of War, undertook to definitively establish Dreyfus’s guilt, and ended up discovering that key pieces of evidence had been forged by Major (now Colonel) Henry (see left). This didn’t change Cavaignac’s mind about Dreyfus, but Henry was imprisoned. He committed suicide the next day.

The day after Henry’s suicide, 1 September 1898, Major Esterhazy (see below), who had been quietly collecting a military pension after his acquittal, fled to England. (He would remain there until his death in 1923.) An ex-lover published letters in which Esterhazy declared his hatred for France and the army, and Esterhazy himself confessed in an interview with a British paper that he had written the original note that had been found in the German Embassy.

Incredibly, the absolute intransigence of the ultra-nationalist “anti-Dreyfusards” was such that even all this would not have been enough to force a retrial. However, there had also been a significant shift in the political landscape that led to the Supreme Court overturning Dreyfus’s conviction in June 1899. Dreyfus was returned to France within a few weeks, still treated as a prisoner even though he was no longer guilty in the eyes of the law. He was held in a military prison for over a month awaiting retrial before the military court at Rennes, in Brittany. The trial began on 7 August 1899, with General Mercier and other military leaders still stubbornly testifying to Dreyfus’s guilt, ignoring the exonerating confessions by Henry and Esterhazy.

One of Dreyfus’s lawyers was Fernand Labori. He had previously defended both Émile Zola and one of the bombers whose execution had prompted the assassination of President Carnot in 1894. A week into the proceedings, Labori was shot in the back while on his way to court (see left) and missed a crucial eight days of the trial. The would-be assassin was never caught.

On 9 September, Dreyfus was convicted of treason again, by a margin of one vote, and was returned to prison. This is the final event depicted in Georges Méliès’s L’Affaire Dreyfus, which was released sometime the following week. The film series, which was in production throughout the second trial, is the most famous of Méliès’s “actualités reconstituées.” It was the longest and most ambitious of his film projects to that point, and was actively engaged in contemporary politics in a way that no film before had been. Although Méliès later claimed that his intentions were nonpartisan, the film’s point of view is unmistakably sympathetic to the Dreyfusard cause. This is also among the earliest examples of a courtroom drama in film.

Ten days after his re-conviction, Dreyfus was issued a presidential pardon on the condition that he admit guilt, which he accepted. Two months later, a bill was passed granting amnesty for any and all criminal acts related to the Dreyfus affair. This included Zola and Major Picquart, but also covered the many actually guilty parties within the military, like Mercier. The Dreyfusards, who had fought so long and sacrificed so much to see true justice done, were outraged, but after years of exhausting political and social upheaval, many simply wanted it all to be over. This was particularly true given the many self-inflicted international embarrassments suffered by the French government, and the upcoming Exposition Universelle of 1900.

Still, “The Affair” lived on. A few years later, the election of a left-leaning government allowed the case to be re-opened once more, and a massive report began to reveal the full extent of the injustice suffered by Dreyfus. In 1906 he was fully exonerated and reinstated into the army with the rank of major.

Zola had died of asphyxiation from fumes from his chimney in 1902. In the 1950s, a French newspaper published a death-bed confession made by a roofer in the 1920s who claimed to have blocked the chimney deliberately. A few years later, during the ceremonial transfer of Zola’s ashes to the Pantheon, Dreyfus was shot in the arm by Louis Gregori, a right-wing journalist who wished to spark a retrial that would once again establish Dreyfus’s guilt. Gregori was later acquitted and hailed as a hero by his fellow French nationalists.

Despite everything, Dreyfus continued to faithfully serve his country. He fought in World War I, along with his son Pierre, and both served with distinction. He retired as a decorated colonel and Officier in the Légion d’Honneur, and died in 1935 (see left).

The Dreyfus affair remained a sore subject long after his death. The secret file on Dreyfus created by the military was finally released to the public in 2013, but some members of the far right in France continue to cast doubt on Dreyfus’s innocence to this day. Films about the Dreyfus affair were banned in France from 1915 to 1950. It has, nevertheless, been the subject of a number of films, including the 1937 Best Picture winner The Life of Emile Zola and, most recently, the 2019 Roman Polanski film J’Accuse.

Screening:

L’Affaire Dreyfus consists of the following scenes:

| # | French Title | English Title |

| 1 | Dictée du Bordereau (Arrestation de Dreyfus) | Dreyfus Court Martial—Arrest of Dreyfus |

| 2 | La Dégradation | The Degradation of Dreyfus |

| 3 | La Case de Dreyfus à l’île du Diable | Devil’s Island—Within the Palisade |

| 4 | Dreyfus mis aux Fers (la Double Boucle) | Dreyfus Put in Irons |

| 5 | Suicide du Colonel Henry | Suicide of Colonel Henry |

| 6 | Débarquement de Dreyfus à Quiberon | Landing of Dreyfus at Quiberon |

| 7 | Entrevue de Dreyfus et de sa Femme (Prison de Rennes) | Dreyfus Meets His Wife at Rennes |

| 8 | Attentat Contre Me Labori | The Attempt Against the Life of Maitre Labori |

| 9 | Suspension d’Audience (Bagarre entre Journalistes) | The Fight of Reporters at the Lycée |

| 10 | Le Conseil de Guerre en Séance à Rennes | The Court Martial at Rennes |

| 11 | Dreyfus Allant du Lycée de Rennes à la Prison | Dreyfus Leaving the Lycée for Jail |

All 11 segments of the series are said to survive. However, the second part (featuring Dreyfus’s military degradation) and the final part (in which he is returned to prison) are apparently unavailable for viewing. Each of the remaining segments is almost exactly a minute long, with the exception of the final court martial, which is a double-length scene.

While these are obviously key moments, the series does not fully function as a traditional narrative. The scenes aren’t necessarily all part of a connected dramatic arc. Rather, they are meant to be recognized and contextualized by people who are already at least somewhat familiar with the events being portrayed. (They may also have been accompanied by live narration in some instances.)

There is quite an extensive cast, with some scenes featuring a few dozen people on-screen. It’s impossible to know how many people are playing multiple roles, and (as is typical of the era) there is no cast list that we can refer to. Méliès himself plays the role of Dreyfus’s lawyer, Labori. This is interesting because Méliès frequently performed the key role in his productions, and his choice of Labori is suggestive of his advocacy for the Dreyfusard cause.

It’s also possible that he did not play the role of Dreyfus, as might have been expected, due to a desire for realism. Méliès is said to have hired an ironworker for the role who bore a striking resemblance to Alfred Dreyfus himself. The casting choice pays off with a notably good performance, whether thanks to good direction or natural talent. In this and numerous other ways, Méliès shows a commitment to verisimilitude that is sometimes lacking even in his other reconstructed actualities. Several scenes clearly used visual references of the events they depict.

Even with no context, the film should not be difficult to follow during the first four scenes, as Dreyfus is shown confronted, arrested, humiliated, imprisoned, and finally shackled. The film doesn’t explain why these things are happening, but the basic narrative is clear. The sympathies of the film seem equally clear in portraying Dreyfus as victim rather than villain.

Scene five is where the film’s story first becomes incoherent without context. Suddenly, there is a totally new character (Colonel Henry), also a prisoner (but a prisoner elsewhere), and he cuts his own throat with a razor. The next scene returns to Dreyfus again. A viewer with no outside knowledge might guess that Henry committed the crime that Dreyfus has been imprisoned for, and kills himself out of remorse.

Given everything that was going on in France during Dreyfus’s imprisonment, the suicide of Colonel Henry seems like an odd choice to connect the scene of Dreyfus shackled and despairing with the scene of his return to France. There is nothing of Picquart’s investigation, the exposure of Esterhazy, or the Zola trial inserted here. Perhaps those all seemed like too much to convey, even for Méliès, in a single minute of silent film.

Henry’s suicide, though, is nothing if not visually dramatic. It is a shocking moment, and one of the more sensational events in the whole history of the case. Certainly it must have made the audience sit up and take notice, and that’s likely why it was included here.

The scene of Dreyfus’s landing is the one concession to Méliès the technical wizard. Dreyfus arrives in France as a storm approaches (or perhaps Méliès is suggesting that he is bringing the storm with him). The use of double exposure adds lightning to the scene (imperfectly but effectively), and stage machinery Méliès had used before to similar effect causes the boats to rock in the background. Finally, as the group prepares to depart, rain begins sheeting down from above.

In the next scene, Dreyfus meets with his lawyers, Labori and Edgar Demange. Méliès (as Labori, the younger of the two) is the second to enter. Then, Dreyfus’s wife, Lucie, arrives and, as the catalog description says, “The meeting of the husband and wife is most pathetic and emotional.”

Here, again, is a scene that seems to exist only to inspire sympathy for Dreyfus. Most of the film deliberately keeps Dreyfus himself firmly in view, as though to remind the audience not to lose sight of his individual plight amidst the sweeping drama that had taken place across several years of espionage and legal wrangling. This, too, feels like a choice with clear motivations.

This scene is followed by two of the three scenes in the series from which Dreyfus is absent, and like the other scene in this category, both depict highly-dramatic, violent events. The first, Méliès’s big scene, shows the assassination attempt against Labori. This scene looks like it is visually referencing the front-cover illustration of the event from La Petit Journal above, albeit from a different angle. After the assailant runs off, Labori’s two companions give chase.

Note that multiple people walk by the fallen Labori as he struggles on the ground and completely ignore him. Méliès may have been suggesting the complicity of the local people, and perhaps of the anti-Dreyfusards at large, in the violence that was directed at Dreyfus and his defenders. This certainly both implies the indifference of many bystanders, and indicts them for it. Even people who refuse to get involved have chosen a side by doing so.

The next scene emphasizes the deep division that existed over this issue, and the volatility of public debate. As reporters gather in the courtroom during a break (Méliès as Labori is clearly visible at the front of the room), an older man stands up and begins haranguing the crowd. In the back left of the group, a woman angrily leaps up to respond. Within moments, the entire room erupts in a fight, as canes and umbrellas are brandished and chairs overturned. Soon, soldiers begin clearing the room, with some wounded limping out last and a few belligerents continuing to struggle.

According to the catalog listing, the older man who stands up at first is Arthur Meyer (see left), of Le Gaulois. Meyer was Jewish, the grandson of a rabbi, but he was a strident anti-Dreyfusard, and had been a supporter of General Boulanger’s ultra-nationalist attempt to grab power in the late-1880s. He converted to Catholicism a few years later, but would continue to be the target of anti-Semitic attacks from people who were otherwise his political allies. He fought a duel with Édouard Drumont, founder of the Antisemitic League of France, although his objection was apparently not to Drumont’s bigotry, but to being lumped in with other Jews. Both men survived the duel, and Meyer later attended Drumont’s funeral.

The woman is Caroline Rémy (see right), an anarchist and Dreyfusard best known by her pen name Mme. Séverine, of La Fronde, a radical feminist publication. Notice that Séverine is the only woman to appear in the scene. La Fronde was particularly notable for being staffed entirely by women, who often had to fight for access to traditionally male spaces so that they could cover topics that only men had written about in the past.

This scene is choreographed very skillfully to convey a chaotic brawl, and the way the mob surges out past both sides of the camera is unusual and dynamic for a shot from this era. The result is one of the highlights of the series, though it is slightly marred by the evident amateurishness of the performers. Note the way the actress playing Séverine very suddenly stops her angry retort and abruptly walks out of frame just as the fight breaks out. There seem to be a few men waving chairs over their heads just off-screen, and perhaps they were meant to move in and obscure her sudden, obviously-rehearsed exit. Note, too, how many of the “combatants” are grinning widely as they hurry past the camera, their faces illuminated sharply in close-up for a brief moment.

Finally, there is the courtroom scene, which would be the proper climax of this drama even if the actual final scene were available to watch. It is the last of several trials that took place as a result of the Dreyfus affair, but in choosing only to depict this one, Méliès retains the gravity of this moment. This is also the scene where the lack of sound or narration is the most keenly felt. At twice the length of all of the previous scenes, it is clearly intended to carry the most weight, but because so much of it is people talking, and we can’t hear them, some of that power may be lost without additional context.

The catalog listing gives an extremely detailed breakdown of the scene, including the names of the key people in it and what they are doing and saying. It also claims that this scene depicts “over thirty” of the key people involved with the trial. The main witness who comes forward to accuse Dreyfus in this scene is General Mercier himself. In all of the positions of power he subsequently held, Mercier never stopped leveraging them to proclaim Dreyfus’s guilt and to oppose his rehabilitation. Here, he takes the stand as Dreyfus’s chief accuser. He is the symbol of all of the Dreyfus affair’s prejudice and injustice represented in one person.

Even without the added context, though, the scene still has powerful moments. We see the full force of the military and the state in opposition to Dreyfus, cloaked in officialdom’s ceremonies and uniforms. Dreyfus’s lawyer (Labori is not present in this scene, as he was recovering from his wounds during most of the witness testimonies, despite his presence in the previous scene) is barely visible, confined to the extreme edge of the frame. Dreyfus is escorted in under guard, and the guard interposes himself between the accused and his advocate.

Without closeups or camera movements of any kind, Méliès successfully conveys Dreyfus’s isolation and his smallness in the face of the forces arrayed against him. And yet, in the scene’s final seconds, we see him stand tall and defend himself publicly with the same sense of urgency, assurance, and dignity that he showed when he was accused privately in the very first scene. Méliès’s point of view is unmistakable here. The Dreyfus affair remains a potent reminder that bigotry and jingoism go hand-in-hand with violence and injustice, and that a free society cannot exist for anyone unless it exists for everyone. Méliès cannot give Dreyfus a voice through the cinema of his time, but L’Affaire Dreyfus puts a human face on his ordeal and forces the audience to see it.

[…] tell a coherent story. This was one of the first films Méliès made after his multi-scene series L’Affaire Dreyfus. But unlike those films, and previous “series” films like La Vie et la Passion de […]

LikeLike

Film History Essentials: Cendrillon (1899) | Moviegoings said this on June 4, 2023 at 1:59 pm |